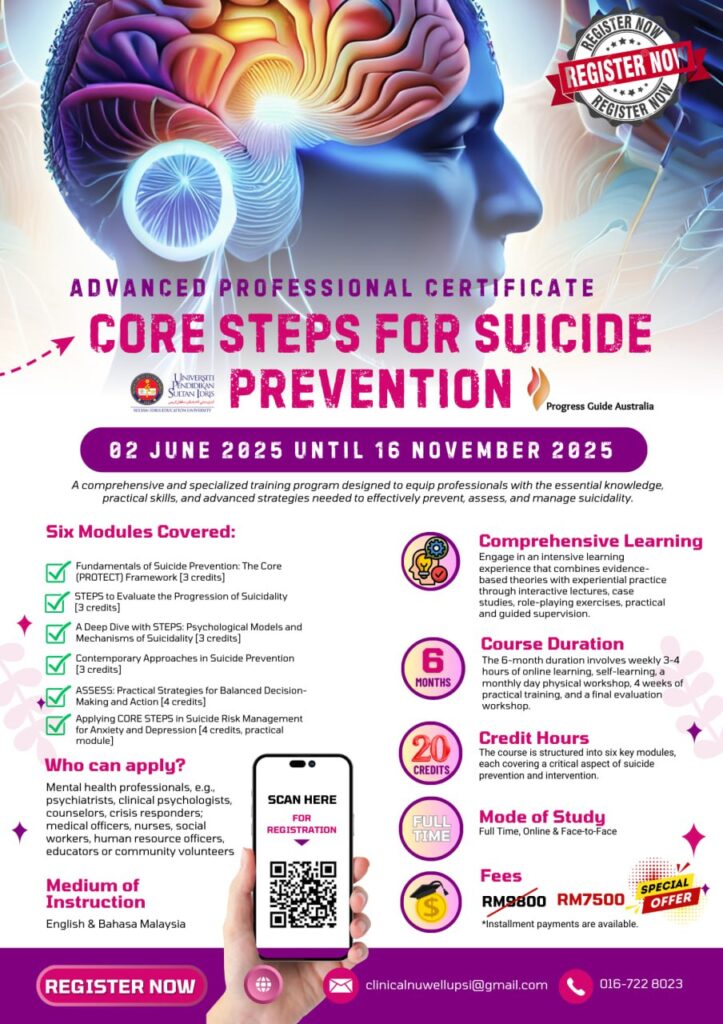

Core STEPS for Suicide Prevention

Advanced Professional Certificate

This groundbreaking professional certificate programme marks a global first in suicide prevention training by integrating three powerful components from the PROTECT Framework. The entire CORE module forms the foundation for the contemporary and innovative STEPS model from the ASSESS module, alongside SAFE from the ASPIRE module. Developed by Progress Guide Australia and delivered by Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris (UPSI), Malaysia, this unique curriculum blends cutting-edge theory with deeply practical application. It brings together the foundational knowledge of suicide prevention (PROTECT), the dynamic STEPS model that maps the progression of suicidality, and the SAFE framework that supports recovery-oriented risk management. Together, these elements offer professionals a holistic and transformational approach to assessment, intervention, and sustainable safety planning.

Capturing Suicidality and its Progression with Precision

In this article we provide details of the novel additions to STEPS how it brings suicide prevention into sharp focus. Imagine the STEPS model as a high-performance camera, meticulously designed to capture the intricate landscape of a person’s suicidality. This camera focuses on key elements: their current stage of suicidality, the source of their emotional pain, the span and fluctuation of their risk, and the potential future trajectory. Each of the 13 models of suicidality acts as a specialised lens, offering unique perspectives that allow professionals to refine their focus with clarity and care. By switching lenses based on the model most relevant to the individual, mental health professionals can tailor their approach—moving away from generic interventions and toward personalised, meaningful care.

The STEPS Trilogy—Volumes One, Two, and Three—serves as an essential guide for professionals aiming to master this art. Together with the 13 models, it empowers clinicians to work confidently across all phases of care, structured through the AIMS framework: Assessment, Intervention, Monitoring, and Step-Up/Step-Down. This integrated approach not only supports immediate clinical needs but also enriches long-term recovery and prevention planning.

Assessment

The STEPS framework, complemented by the 13 models, enriches professionals’ ability to conduct precise and compassionate assessments. These models offer a wide array of perspectives—ranging from biological predispositions to interpersonal distress, fluid vulnerability, and sudden shifts. They help clinicians move beyond static risk labels to understand the lived experience of suicidality. This approach enables professionals to capture both cross-sectional snapshots and longitudinal narratives, ensuring a deeper understanding of the patient’s current position along the continuum—from Life-in-Motion through ideation to action and finally to Safe Recovery.

Intervention

Each model brings distinct insights into predisposing, precipitating, perpetuating, and protective factors. By layering these onto the STEPS journey, clinicians can co-construct a biopsychosocial and cultural map of the patient’s pain and resilience. This allows for dynamic, individualised safety planning and therapeutic intervention. Whether the goal is to reduce the intensity of emotional pain, disrupt cycles of entrapment, or enhance connectedness and hope, the models provide actionable strategies that are developmentally and culturally sensitive. This moves safety planning beyond checklists—toward compassionate, creative, and collaborative care.

Monitoring

Suicidality is not static—it ebbs and flows. The 13 models help professionals and patients alike understand these fluctuations by identifying what influences risk over time. With the STEPS framework as a compass and the models as interpretive guides, clinicians can support patients and families in developing self-monitoring strategies that foster awareness and agency. This is particularly vital when patients are not in continuous contact with services, ensuring they are better equipped to manage distress, identify early warning signs, and seek help when needed.

Step-Up or Step-Down

By understanding a patient’s movement across the STEPS continuum and interpreting it through multiple models, clinicians are better equipped to make informed decisions about when to escalate or de-escalate care. This responsiveness allows services to be both proactive and proportionate, ensuring that support is timely, appropriate, and aligned with the patient’s evolving needs and risks.

Which Lenses Do You Possess?

In the following section, we examine the unique contributions of 13 models of suicidality. Each model offers a distinct lens through which to understand the development, maintenance, and resolution of suicidal thoughts and behaviours. By exploring these frameworks, we gain deeper insight into the different stages of suicidality, enhancing our ability to assess, intervene, and support individuals with precision and compassion.

The Stress Vulnerability Model’s unique contribution to understanding suicidality lies in its elegant simplicity. It elucidates how the interaction between inherent vulnerabilities (like genetics or temperament) and external stressors (such as life events) can precipitate mental health crises. This model’s versatility extends beyond suicidality to conditions like depression, anxiety, and psychosis, making it a foundational lens for understanding how different stressors impact individuals’ mental health.

The Stress-Diathesis Model’s unique contribution lies in its emphasis on the interplay between biological predispositions and environmental stressors. It brings the role of neurotransmitters, genetics, and other biological factors to the forefront, providing a more intricate understanding of how these elements interact with stress to influence suicidality. This holistic perspective enriches our understanding by incorporating the biological underpinnings of mental health, offering a more comprehensive framework for intervention.

Shneidman’s Cube’s unique contribution lies in its shift from categorical risk stratification to a continuum-based approach. By illustrating how distress can progress across the axes of pain, perturbation, and stress, it empowers professionals to recognise that even small changes can significantly reduce risk. This model moves us away from absolutes, demonstrating that progress is possible through incremental steps, providing a hopeful, actionable framework for suicide prevention.

Beck’s Cognitive Triad uniquely contributes to understanding suicidality by offering a cognitive roadmap focused on the negative view of self, world, and future. This model shapes our understanding of the predisposition phase, highlighting how entrenched negative thought patterns can lead to suicidal ideation. It also presents opportunities for intervention through cognitive reframing and restructuring. By addressing these thought patterns, professionals can develop targeted interventions, making it pivotal for early-stage safety planning and cognitive-based therapies.

Baumeister’s Escape Theory uniquely contributes to understanding suicidality by focusing on the role of self-blame, inadequacy, and failure. Particularly relevant during the intention stage, it explores how individuals may attempt to escape aversive self-awareness through suicidal behaviour. This model highlights how feelings of failure and self-perceived inadequacy can drive suicidal intent, providing crucial insight into how these cognitive patterns can be addressed therapeutically, and offering targeted avenues for intervention.

Linehan’s work, particularly the Reasons for Living vs. Reasons for Dying model, provides profound insight into the internal struggles of individuals, especially those with borderline personality disorder. By illuminating this internal battle, it opens avenues for motivational interviewing to shift the balance towards life-affirming choices. Concepts like the rational mind, emotional mind, and wise mind further enrich these conversations, helping individuals recognise states that lead toward suicidality. Additionally, chain analysis offers a detailed exploration of triggers, antecedents, behaviours, and consequences, providing not only understanding but also tailored intervention strategies for staying safe.

Williams’ Cry of Pain Model is pivotal for understanding the transition from ideation to action, particularly in its exploration of defeat and entrapment. Building on Beck’s Cognitive Triad and Shneidman’s notions of psychic pain, it frames suicidality as a desperate cry for relief. The model’s unique contribution lies in its clear framework for understanding entrapment, presenting suicidality as a perceived lack of escape from unbearable pain. This perspective not only deepens our comprehension of the suicidal mind but also underscores the necessity of interventions that address feelings of defeat and offer pathways out of entrapment.

Van Orden’s Hierarchical Taxonomy of Suicide categorises risk factors into dispositional, acquired, and practical, making it a powerful tool for clinicians across all phases, particularly predisposition and ideation. It underscores that interventions can occur at any stage based on identified risk factors. By offering a structured approach to risk, it not only informs clinical practice but also lays the groundwork for later models like the Integrated Motivational-Volitional Model, enhancing our understanding and intervention capabilities throughout the suicidality spectrum.

Joiner’s Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide offers a straightforward yet powerful framework for understanding the transition from ideation to action. By integrating the concepts of thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and acquired capability, it distils complex dynamics into three core forces driving suicidality. The model’s simplicity and clarity have made it instrumental in shaping contemporary suicide prevention strategies, providing a clear pathway for clinicians to assess and intervene in suicidal behaviour.

The Integrated Motivational-Volitional Model offers a comprehensive framework that spans the entire spectrum of suicidality. By dividing the process into three phases—predispositional, motivational, and volitional—it illuminates the moderators that drive progression from one phase to the next. These moderators offer crucial intervention points, enabling targeted safety planning, monitoring, and prevention strategies. Though complex, its depth and breadth provide professionals with unparalleled insights into the complexities of suicidal behaviour, making it an invaluable tool for comprehensive assessment and care.

Fluid Vulnerability Theory is exceptionally advanced, focusing on the dynamic nature of suicide risk. It uniquely differentiates between acute and chronic risks, offering insights into baseline risk variations among individuals. This model clarifies how multiple attempters possess higher baseline risks, while single attempters may require more significant stressors to escalate risk. By highlighting the interplay of cognitive, affective, physiological, and behavioural factors, Fluid Vulnerability Theory provides a nuanced understanding of how suicide risk fluctuates, making it an invaluable tool for comprehending and addressing suicidality’s complexity.

The Cusp Catastrophe Model offers a highly sophisticated understanding of suicidality, focusing on the importance of specific triggers for specific individuals. It demonstrates how crises can emerge abruptly, even when everything seems stable. By explaining stable, dysregulated, and discontinuous changes, it clarifies why some individuals appear fine until a sudden crisis occurs. This model is crucial for explaining suicidal attempts that seem unanticipated, offering a framework to understand the seemingly sudden onset of suicidal crises.

Conclusion: Framing the Future of Suicide Prevention

Like any skilled photographer, a mental health professional must not only possess the right camera and lenses but also know when and how to use them. A wide-angle lens offers breadth—capturing the life-in-motion context and broad psychosocial landscape. A telephoto lens allows us to zoom into high-risk periods like moments of acute intent or recent trauma. The macro lens draws our attention to subtle details—those fleeting thoughts, quiet shifts, and barely audible cries for help that might otherwise go unnoticed. Filers and polarisers can provide crucial cultural context in engaging with a person’s narrative of pain. Mastering the STEPS framework and its 13 lenses requires more than theoretical knowledge—it demands practice, presence, and precision.

That is why our training does not stop with models and frameworks. Through immersive case studies, interactive role plays, and reflective debriefings, the STEPS training and masterclasses are designed to build confidence and competence. These practical components are central to our professional certification program in Malaysia, delivered in collaboration with Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris (UPSI). This programme equips mental health professionals with both the width of systems thinking and the depth of clinical nuance, ensuring they are prepared not just to assess risk, but to co-create safety, hope, and recovery with those they serve.

In the end, it’s not just about having the best equipment—it’s about cultivating the eye, the timing, and the human connection to capture what truly matters.