14 | AWARE 1 – Appraise Clinical Decision – ANXIETY

- Posted by Manaan Kar Ray

- Categories Weekly PROTECT Podcast

- Date April 22, 2022

Transcript

Host: Good day, this is Mahi, your host, we are on to episode 14 and about to dive into the AWARE framework. We began the ASSESS module in Episode 13, Manaan provided an overview and we started looking at attitudes to suicide and why awareness regarding where one stands is so important in terms of care delivery. Not right or wrong attitudes, just awareness. We asked you all to pause and reflect, where do you stand on the question, should suicide always be prevented, under what circumstances might you consider suicide for yourself if at all, is suicide a sin, or is it a right, is suicide cowardice or does it courage, is suicide a selfish act. Manaan, we might have raised more questions than we answered and even if our listeners did not get answers and just thought about different perspectives, I believe we succeeded. Do you agree?

Expert: Absolutely, as you said no right or wrong answers, just awareness. If you think suicide is unequivocally wrong, you may be judgemental and that may impact therapeutic alliance and relational safety, if you think it should be a permissible act then you may not take definitive action to save a live and be considered negligent. There are pros and cons either way. Be aware, awareness matters cause your awareness of your attitudes impact your decisions.

Host: If you haven’t listened to episodes 13, now might be a good time to do so as it also provides an overview of what will be covered in the 6 chapters of the ASSESS module. Also in episode 12, we talked about progress to practice coming from 3 shifts: prediction to prevention, past to future and deficits to assets. So keep that at the back of your mind. As usual for the key messages and for the messages in images either go to the podcast blog at www.progress.guide or you can get the PROTECT Guidebook from Amazon to read along. The images are particularly helpful for visual learners and help with retention. Also do not forget to rate us on spotify or apple podcast, it helps us get the word out. Ok let’s get started with the AWARE framework, tell us a little bit about the origin of the framework.

Expert: To put AWARE into context I have to share Ed’s story. Whatever I am sharing is in the public domain and comes primarily from the coroner’s hearing. I also took Steve Mallen, Ed’s father’s permission to frame AWARE in the context of Ed’s death. So, Feb 9 2015, 3.30 pm Edward Mallen, an academically and musically gifted 17 year old Cambridge resident threw himself in front of a train. On the 22nd of January he saw his GP and shared his suicidal thoughts. The GP was extremely alarmed and requested a 24 h assessment. In the triage that followed, the telephone practitioner felt convinced with what Ed said that he could keep himself safe, in his own words at the inquest ‘He assured me that this was not something he was going to do’ and the 24 hr assessment request was downgraded to a 7 day assessment. He was assessed face to face by a crisis team practitioner on the 26th of Jan who felt similarly reassured regarding safety. On 6th February he saw a private psychologist where he spoke eloquently and described future plans. He was brighter after the appointment and the next day played on the xbox with his brother and went to the pub with his friends. The day after that we have his tragic death on the train tracks. At the surface it seems everyone did right by Ed, but how did Ed pass away despite so many touch points with services.

Host: This really is sad, a life full of potential lost to suicide.

Expert: Every death to suicide is tragic but the loss of a young person always hits a team quite hard. It got us thinking about decision making. Ed’s story truly highlights how challenging clinical decisions can be. Assessors have to decide based on the information in front of them and make predictions about the future. The question arises ‘do assessors consider all the information in a logical factual way or are there other unconscious influences on their decision making’. So in the Cambridge crisis team which was involved in Ed’s assessment we conducted a qualitative study trying to identify what influences the decisions that are made.

Host: Given the podcast is being heard in over 50 countries many of our listeners may not know what a Crisis team is.

Expert: Fair point, in Australia the closest semblance will be the Acute Care Team. Not sure what it will be in the US. In the UK, Crisis Resolution and Home Treatment Teams are at a critical juncture in the care pathway of patients in suicidal distress. They gatekeep all inpatient beds and provide an alternative to admission. Following the gatekeeping assessment, outcomes involve inpatient psychiatric admission, intensive home treatment support, onward referral for continuing care to a community mental health team and at times feedback to the referrer that the patient does not meet the threshold for secondary care. In many countries Emergency Departments have this decision making role, I guess you get the picture, you can think of the team that assesses people in suicidal distress and decide where to from here.

Host: OK so you conducted a qualitative study on staff in the Cambridge Crisis team.

Expert: Yes, we conducted semistructured face to face interviews of the Multidisciplinary staff of the crisis team. Participants discussed an assessment they have carried out within the last 24 hours and using a laddering technique of repeated “why or why was that or asking so what” the reasons behind the clinical decisions were explored. The goal was establishing how decisions relating to risk and treatment needs were arrived at. Transcripts of the interviews were then thematically analysed.

Host: So what did you all find.

Expert: The results showed that suicidality was the primary reason for referral. As expected managing patient need in terms of treating the symptoms or mitigating the risk was the primary driver for decisions. Statements like “She was admitted for her own safety, she was unpredictable, it would have been difficult to manage that in the community at that time… Admission was the right decision”

Host: Surely you did not need a study to tell you that patient need and risk were the reasons behind the clinical decisions.

Expert: Ah ha this is where it gets interesting. The study also revealed that during the assessment, clinicians collated considerable information, but these assessment findings were not processed uniformly. Patients with similar need and risk profiles could end up getting rated very differently in terms of risk and could end up in diametrically opposite treatment pathways, from being admitted to signposting to non-governmental agencies. A range of mental shortcuts were used. Clinicians described these shortcuts as common sense or educated guesses. However, they were often unaware of these processes and they came to light only when their judgment calls were directly bought into question.

Host: So, these are like heuristics.

Expert: Yes that is a nice word to describe the sum total of all the stereotyping, rule of the thumb, gut instinct, instinctive judgement, common sense and educated guesses, after a few annoying rungs of the ladder of assessors being asked and why did you decide that and why was that and can you explain that a bit further, you hit a wall where the clinician goes because that’s what you do in that situation, and one can see that there is a heuristic or a mental shortcut has kicked into play,

Host: I guess this mental shortcut could be previous knowledge, experience, beliefs, biases and/or a combination of all of those.

Expert: Yes that’s correct. Based on these findings we constructed the framework called AWARE with 5 themes which we will now cover systematically.

Host: Why do we need such a framework?

Expert: Well AWARE pins down the key drivers of Clinical Decisions

AWARE protects against undue influences in the act of clinical decision making. It is intended to make practice safer, its use in clinical supervision or multidisciplinary case reviews should bolster practice by making individuals and/or teams who assess people in suicidal crisis, mindful of the implicit effect of the AWARE factors. AWARE promotes reflection in action, on action and for action. There is a specific focus on clinical decision making however it also supports a critical contemplative process of evaluating one’s, attitudes, beliefs, values, thoughts, feelings, behaviours and learning needs in the context of clinical work, evidence based practice and professional culture.

Host: And all of this is achieved by highlighting subjectivity in Clinical Assessments

Expert: Yes that is one very important aspect of AWARE, there is an assumption that clinicians make decisions based on objective risk-related findings in an assessment. As I was saying that clinicians accounted for the variation in their decision making by using terms like “commonsense” and “gut instinct”. These mental shortcuts in decision making will seem diametrically opposite to decisions being firmly rooted in clinical findings from a holistic bio-psycho-social assessment that is also drawing on the person’s cultural, environmental and spiritual context. Other studies from Prof Bhugra’s group also highlight a similar lack of awareness of errors and biases that may creep into clinical decision making (Bhugra, Mallaris, & Gupta, 2011; Bhugra, 2008). AWARE aspires to make the implicit explicit.

Host: You mentioned in the ASSESS overview your preoccupation with acronyms, I am assuming the five heuristic themes that influence information processing fit neatly into an easy to remember acronym – AWARE.

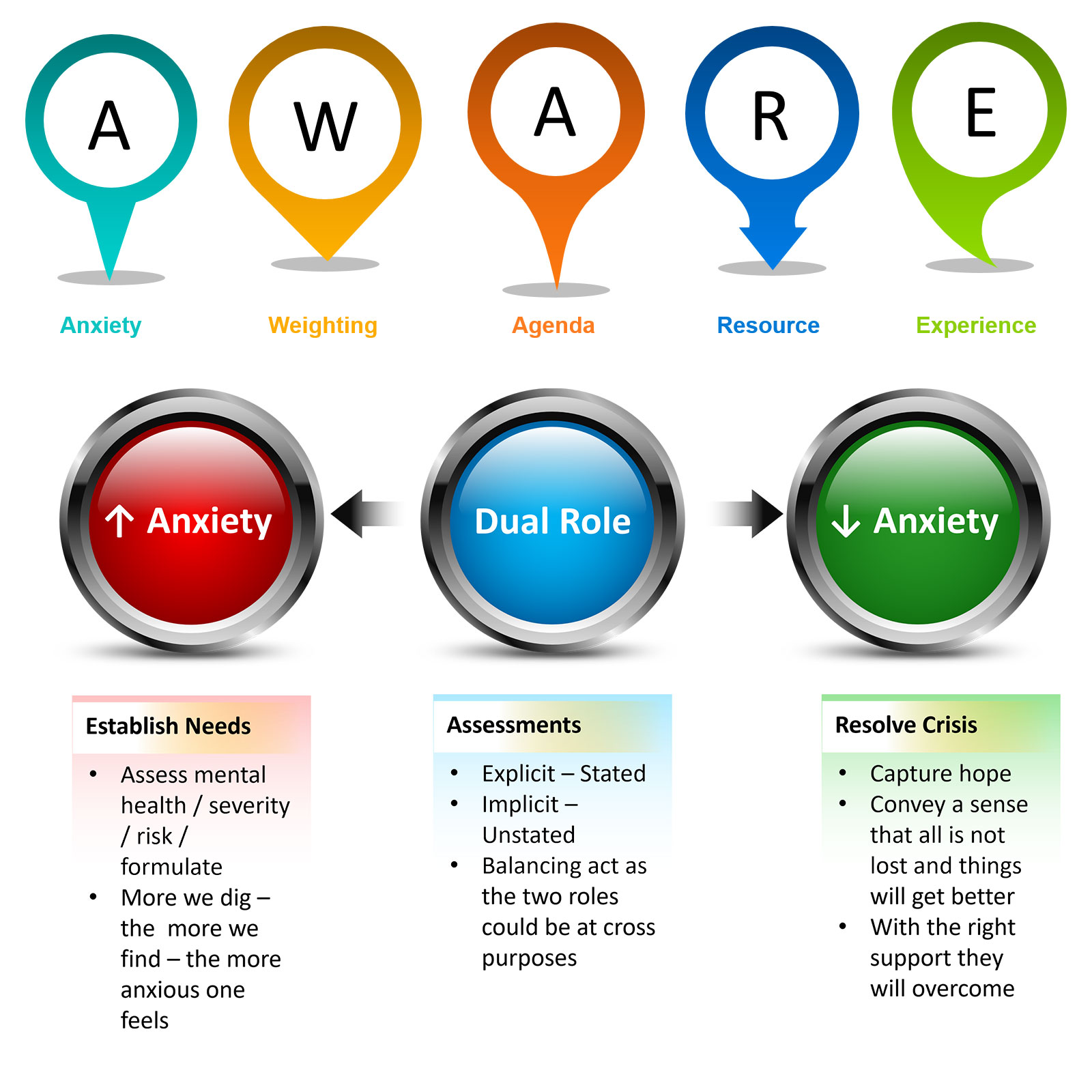

Expert: Of course they do, A is for Anxiety (generated/diffused in):

- Patient

- Family/carer/friend

- Referrer

- Triaging/assessing practitioner

W for Weighting (of symptoms elicited):

- Diagnosis (comorbidity – personality disorder/alcohol or substance misuse)

- Course of illness (acute/chronic/acute on chronic)

- Factors considered outside core remit (relationships/finances/accommodation/employment/family – carer availability)

A for Agenda (elicited in):

- Referrer

- Patient

- Family

- Practitioner

- Team

R for Resources (identified or not):

- Beds

- Home treatment capacity

E for Experience (generalised from):

- Same patient to different presentation

- Other patients from the same diagnostic group

- Other patients from the same demographic profile

- Past adverse events

Host: A for Anxiety, W for Weighting, A for Agenda, R for Resources and E for Experience, I am assuming we will explore each of these in detail

Expert: I think we may only have time to look at Anxiety today but yes we will work our way systematically through each factor.

Host: So tell us more about how anxiety influences clinical decisions.

Expert: Ok consider the following two statements by assessing clinicians from the AWARE study:

First one is: “Well sending him back to the referring community team was straightforward, he was able to engage in it (the assessment) despite the difficulties with his symptoms”

The Second statement: “…There was obviously some urgency to it (admit). He had strong thoughts of taking an overdose the previous day… and his wife had to take time off work because she was concerned about his help seeking”

Host: In the first, the patient is discharged home and in the second, the patient is admitted.

Expert: Yes, but both statements were made by clinicians who had assessed similar patients in terms of symptom severity. So in a young agitated, suicidal male with limited protective factors, willingness to engage trumped symptoms of severe depression. Essentially the expressed desire to engage diffused everyone’s anxiety and became the rationale for not taking the person on for intensive home treatment support. In a very similar presentation from the second person, a diametrically opposite decision to admit to the hospital was made as anxieties were quite high due to his lack of help-seeking and engagement.

Host: What you are saying is unresolved anxiety in the assessor or the family for that matter resulted in the decision to admit whereas where anxiety was addressed the person was managed at home.

Expert: Yes but both were very similar in presentation. The decision was not determined by symptom severity or complexity or need, it was determined by how much unresolved anxiety was there.

Host: I get that anxiety is perhaps more a gut instinct than a cognitive one, but surely anxiety is a reflection of how much risk is left unaddressed in the clinician’s mind like the one with good engagement surely that is an indication of the risk being lower.

Expert: True, good engagement is a sign that you can work with the person towards recovery but is it enough to send someone back to the referrer and not even to take them on for intensive support given you are not admitting them. In someone with severe agitated depression how much would need to change for them to tip over into a suicidal state or make an attempt, does engagement really trump severe symptoms of agitated depression?

Host: Ok so what you are saying is that engagement here will form part of the risk formulation but does not even come close to explaining the actual clinical decision not to take them on for intensive home treatment if not admitting them.

Expert: That’s correct, what engagement does do is it diffuses the anxiety in everyone and provides a rational for not taking the person on, whether anxiety resolved or unresolved has a major bearing on the clinical decision and the next steps in terms of treatment for the person.

Host: This makes Anxiety the first AWARE factor. Is there a reason why you have chosen it to be the first?

Expert: Because of how important it is. In the midst of a suicidal crisis anxiety is present in everyone. The referrer feels less anxious knowing somebody else is dealing with the crisis, the patient and family feel reassured if they get the right help, and the assessor’s anxiety settles when the patient says they can keep them self safe.

Host: Thus being aware of the impact of anxiety on the assessment process is crucial.

Expert: If you stand back from the assessment of a person in suicidal crisis and looked at its purpose, you will discover that assessors have a dual role. The first is to assess, that is what the name suggests, now the more you dig, the more risk you find and this increases anxiety in everyone. As risks get explored and identified the more anxiety there is overall. The assessment has also got an implicit second role. That is to contain the crisis by capturing hope; conveying that things will get better, this decreases anxiety in everyone.

Host: I see what you mean, a good assessment will highlight all the challenges ahead and that will make others anxious but somehow the assessment also has to be containing, and you have talked about the explicit promise of hope and recovery in the CORE module quite a bit. This must be a difficult balancing act.

Expert: Yes it is, a very difficult balancing act, as the two purposes of an assessment, one explicit and the other implicit, could be at cross purposes. Many clinicians feel ill-equipped to deal with their own risk findings; thus, they often veer away from enquiring too deeply about suicide in the fear that if they acknowledge a risk, they will have to manage it without the competencies or resources to do so (Cole-King & Lepping, 2010).

Host: Yes, you have mentioned that in your training, even experienced clinicians say that if I use all the techniques in the ASSESS module like B4Now and clearly document the risk that I discover that they will be left exposed if things went wrong post assessment.

Expert: Yes that comes up a lot and nothing can be further from the truth, cause there is a longer more convoluted way to managing one’s anxiety which is to do a thorough assessment that exposes all the risks so that they can be addressed. Instead, clinicians drift towards minimising the danger and use recovery language to instil hope and convey all is not lost. Generally, hope vending is protective and anxiety containing but it is not a replacement for through risk exploration.

Host: So what should clinicians do.

Expert: Well for starters be aware of ones anxiety levels and the impact it has on the assessment interaction. Actively seeking reassurances like ‘Can you keep yourself safe’ without a true appreciation of the dynamic nature of risk may create a misleading veneer of safety. The reassurance relates to the hope captured by the clinician, but the person may remain poorly prepared for emergent adversities (‘what if’ scenarios), a phenomenon Shea calls premature crisis resolution (2009).

Host: Yes those safety reassurances don’t change the risk as the challenges still exist for the person, but they do bring the anxiety down in the professional and provide a better nights sleep.

Expert: Those reassurances are misleading and I actively tell my students not to go seeking them, they are a pointless exercise, make the assessor feel better and stops them from doing the essential safety planning.

Host: But I guess it is easy to understand why assessors ask those questions.

Expert: Absolutely, professionals have the difficult task of striking a balance between actions that increase and decrease anxiety not just for the person and their family but also for themselves. What we found in our study was that up to a tipping point, anxiety was managed by rationalising risk-taking as positive risks in line with recovery philosophy. Beyond it, anxiety was contained through conservative and restrictive treatment options such as an inpatient stay (Lombardo et al., 2019). The threshold is different for each clinician but every clinician has a tipping point, the degree of unresolved anxiety is perhaps the most important influencer of the assessment outcome.

Host: So you are saying that anxiety works both ways, sometimes anxiety that has been resolved help us take positive risks and when it is not, we may end up looking for justification as to why it is ok to take restrictive measures like inpatient stay.

Expert: That is absolutely correct. We see what we want to see. This is a theme that will recur through the entire AWARE framework. Anxiety is not a nice emotion to experience, so there is an unconscious driver to decrease anxiety not just for the person in distress but also for the assessor themselves; this is done through seeking reassurances related to safety. However, assessors do know that risk is dynamic and can change quickly. However, if they keep exploring, they will feel anxious again. The shallow blanket statement ‘I can keep myself safe’ is used to rationalize away why not to explore the dynamic aspect of risk fully. On the other hand a highly anxious clinician may overlook all the potential protective factors and the strengths in the person as they struggle to manage their own anxiety. To bring progress to practice it is so important to not just see what we want to see, but make decisions that are based on the facts of the presentation.

Host: Do you see what you want to see, or do you dare to open yourself up to all that is there to see, the risk, the safety concerns on the road ahead as well as the person’s natural strengths and their natural circle of support. This brings us to the end of episode 14, today you heard about Ed’s story and all the touch points he had with services and still such a tragic outcome. The story highlights some of the challenges of working with people in suicidal distress and how dynamic risk is. Do we stop and think about how risk might evolve in the near future or is it just a cross-sectional opinion in the here and now. Do you in your practice seek out safety reassurances? Pause and think, does it really impact the dynamic risk, the person feels safe in your presence but what happens when they leave your consulting room. What do you think? Are safety reassurances meaningful or are they a pointless exercise designed to give you a better night’s sleep? What do you think about them, where do you stand? Tweet your thoughts about anxiety in the face of suicidal distress at #GuideProgress. It helps get the word out about the podcast to more professionals and challenge the stigma related to suicide and mental health challenges. You can email your thoughts to us at admin@progress.guide with your suggestions and comments particularly if you have questions and want us to cover certain topics in the discussion. In the next episode, we will go through the other factors in the AWARE framework and the two mental spaces, rational and rationalising, knowledge that will transform your practice. You can access all the information at www.progress.guide. You can connect with Manaan on Linked in, or follow our linked in page by searching on linked in for progress.guide. We are also on twitter and YouTube. Our twitter handle is @GuideProgress. As usual please do follow the podcast, there will be weekly episodes every Friday and share it with your colleagues. Your ratings will help get the word out so please don’t forget to rate us on Spotify, apple podcasts or audible or whichever channel you are listening on. Helping healthcare professionals become aware of their own anxiety in the assessment process is an essential step in creating a workforce that is self-aware. Remember together we can make a difference. Tune in next Friday and we will explore the other factors in the AWARE framework. Thank you for joining us today and keep spreading the word.

You may also like

19 | Creep Crash Crawl

18 | AWARE 5 – Experience