10 | Empathy in Action III – Values of Relational Safety

- Posted by Manaan Kar Ray

- Categories Weekly PROTECT Podcast

- Date March 11, 2022

VALUES INTO ACTION - The Process of Translation

Host: Good day, I am Mahi, your host, we have made it to the final episode of the CORE module, Part 3 of Empathy in Action. In the next episode we will be begin with the ASSESS module. Today though, we will be diving deep into the 5 values of Relational Safety, courage, curiosity, compassion, collaboration and commitment and translating these values into action. In the previous episode, you learnt about the equation of empathy in action, empathy in action = cognitive empathy + emotional empathy + empathic concern. We made the initial link between values and actions and provided words for the pain relief dialogue. As usual the transcript and the media will be on the blog at www.progress.guide or you can get the PROTECT Guidebook and Workbook from Amazon to read along. Let’s begin and translate each of these values into action. Manaan, in the guidebook you write that the courage to suspend the desire to help is one of the hardest values to practice.

Courage:

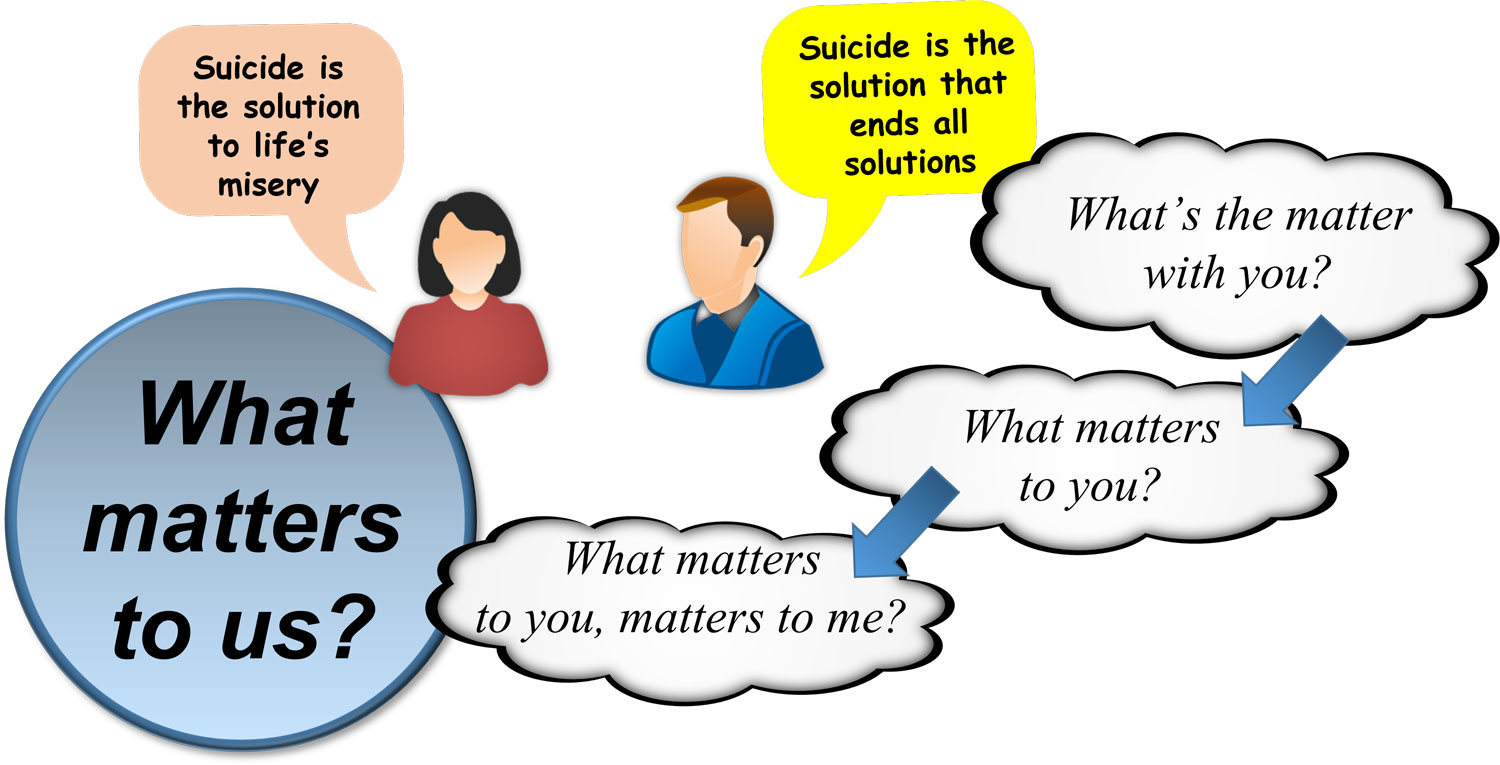

Expert: Indeed, health professionals are hard wired to detect and diagnose problems and look for solutions. They want to relieve the person they are treating of their suffering. Partly this is their training, partly these are societal expectations.

Host: So, you are saying the expectation is you are the expert; fix it.

Expert: Yes and to make matters worse, human beings can listen to 500 words/minute, but normal speech is at 225 words/minute. A person in suicidal distress might speak considerably slower than this. Even with normal speech, there is an unused cognitive capacity of 275 words/minute. This primes the mind to wander in the search for solutions. Being present in the moment is tough. It has to be repeatedly practised, akin to creating muscle memory in a pianist or a tennis player. It is normal for the mind to go looking for rapid options for pain relief; when that happens, acknowledge that you have drifted and mindfully bring yourself back to the person’s story, repeat the process over and over again.

Host: So, if you have jumped to solutions that is just human nature, but you also speak in your courses about how a professional may waver in the courage it takes to suspend the desire to help.

Expert: Yes, but as you say the desire to help is a human phenomenon and not unusual at all. Hold back a bit longer and just be present. Brene Brown has a short animation on YouTube on empathy in which she makes the point, that for a person in a pit of darkness, rarely does saying anything makes it better. What does make a difference is connection. And that connection can be fostered through your presence in their darkness. Your presence will draw out the strengths in the person that will help them navigate through this and the many storms yet to come. Your solutions maybe will help with this storm, but the opportunity for the person to learn and grow from the current adversity will be lost; learning that can contribute meaningfully to futures solutions is priceless. Thus, practice being present, just present, momentarily suspend your desire to help. Practice makes perfect.

Curiosity:

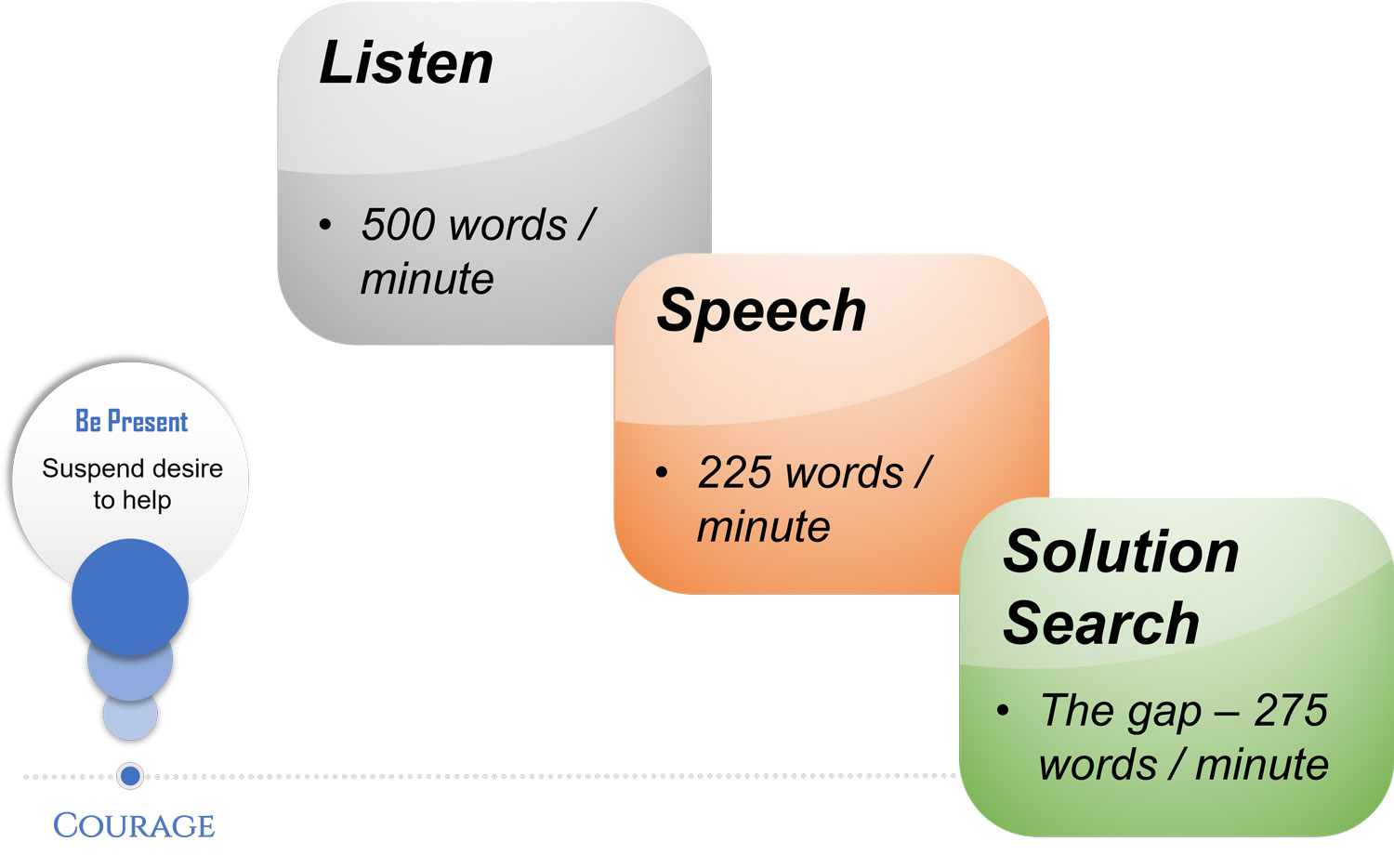

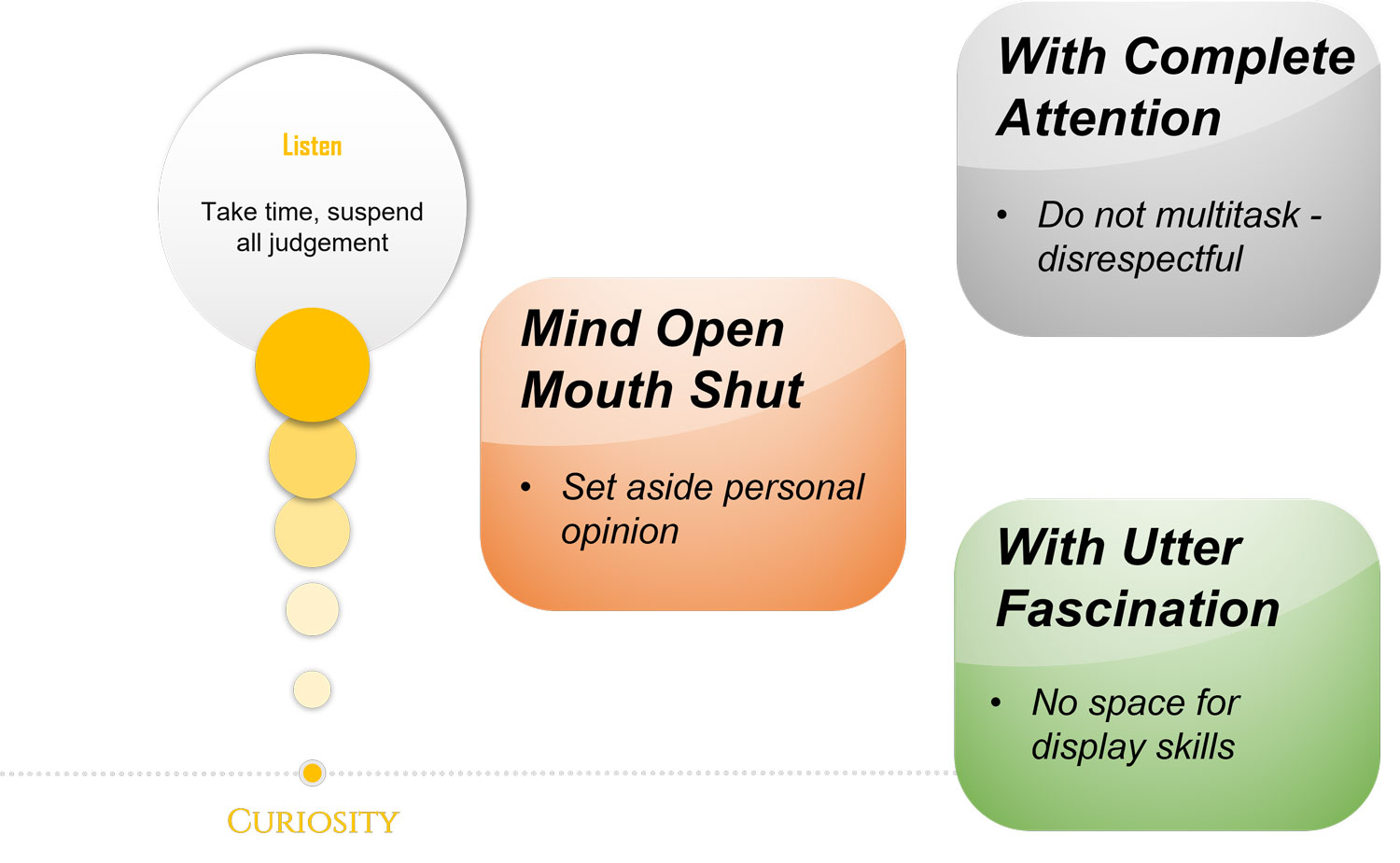

Host: For the second value Curiosity, in the PROTECT Guidebook you use the catch phrase listening with fascination.

Expert: Yes , mind open, mouth shut, listen up. Listen with fascination and give the person’s narrative your complete attention. Emergency departments, psychiatric wards, outpatient mental health clinics are all busy places with multiple demands on the professional’s time. Listening to a person’s suicidal distress is often at the cost of other tasks and activities that need to be completed. Sometimes it will feel that the patient is in the way of doing your job. Mindfully remind yourself that the patient is not in the way, patient is the way.

Host: Patient is not in the way, patient is the way?

Expert: This was a phrase I picked up from John Nicholson, he was the Chaplain at Fulbourn Hospital in Cambridge. I was the Clinical Director there leading the PROMISE project to reduce coercion in care. He was a very humble man and would say profound things. In one of our discussions he highlighted to me how on a busy ward when a nurse is juggling a million things, a simple request like can I have my phone charger or a question like when will my medication be ready to take home, may feel like that the patient is getting in the way of the nurse doing the job, but looking after the patient’s need is the job. He wrote up a short article for us, patient is not in the way, patient is the way. One thing I learnt from the interactions I had with him was the importance of pause and take time; if need be, make time. Listen with genuine curiosity, be interested.

Host: Taking time is so important, after all sharing one’s suicidal distress takes a lot of courage,

Expert: Exactly, so show the person the respect you would expect if you were the one sharing. Try not to multitask; leave your phone or pager alone. If there is a probability that you are going to be interrupted, make sure that you mention it upfront to the person. Small gestures like this will go a long way to show that you care.

Host: That’s all very well but how does one curb the desire to instantly make it better and just listen?

Expert: Be mindful that as you listen to the story, there will be a strong desire to silver line the darkness that envelopes the person. Suspend all judgement, and if an opinion has developed within you that begins with “at least”, keep it to yourself. At least your family are quite supportive… at least you still have your job… at least… These well-intentioned statements do not have the expected positive effect. Sometimes they add to the guilt about feeling miserable and self-centred; at other times, it makes the person feel invalidated and not listened to. So in your speech stay vigilant of any attempt to silverline, these will be statements that begin with atleast, you believe you are being helpful but actually one comes across as fairly judgemental, in our courses we often carry out communication exercises to practice this, bottom line is if you want to pontificate and come across as judgemental go and write a blog, even if that is not your intention, good intentions are not enough, you have to practice curbing your desire to silver line their current psychological pain.

Host: Yes, if the pain is so intense to cause suicidal distress I am assuming such statements wont remedy the pain

Expert: As Brene Brown says rarely does saying something change the pain; listen instead. If you don’t know how to respond to their profound pain, share that and go back to listening. You are much more likely to connect at a human level than any “at least…” silver lining you can conjure up.

Host: And does body language play a part in conveying your curiosity.

Expert: Nonverbal communication and body language have their place, but we are of the opinion that if you are genuinely listening, the open palms, the forward lean, the 30 degrees head tilt are all redundant. Your curiosity and heartfelt attempt at making sense of the person’s pain will shine through. Putting it bluntly and this is my opinion if you are truly listening you don’t have to show that you are listening, you don’t have to act it out, it will be self-evident and the converse is also true, if they have not got your complete attention, does not matter which non-verbals you display, people know that you are not in the room with them. Be in the room, be present and listen with fascination.

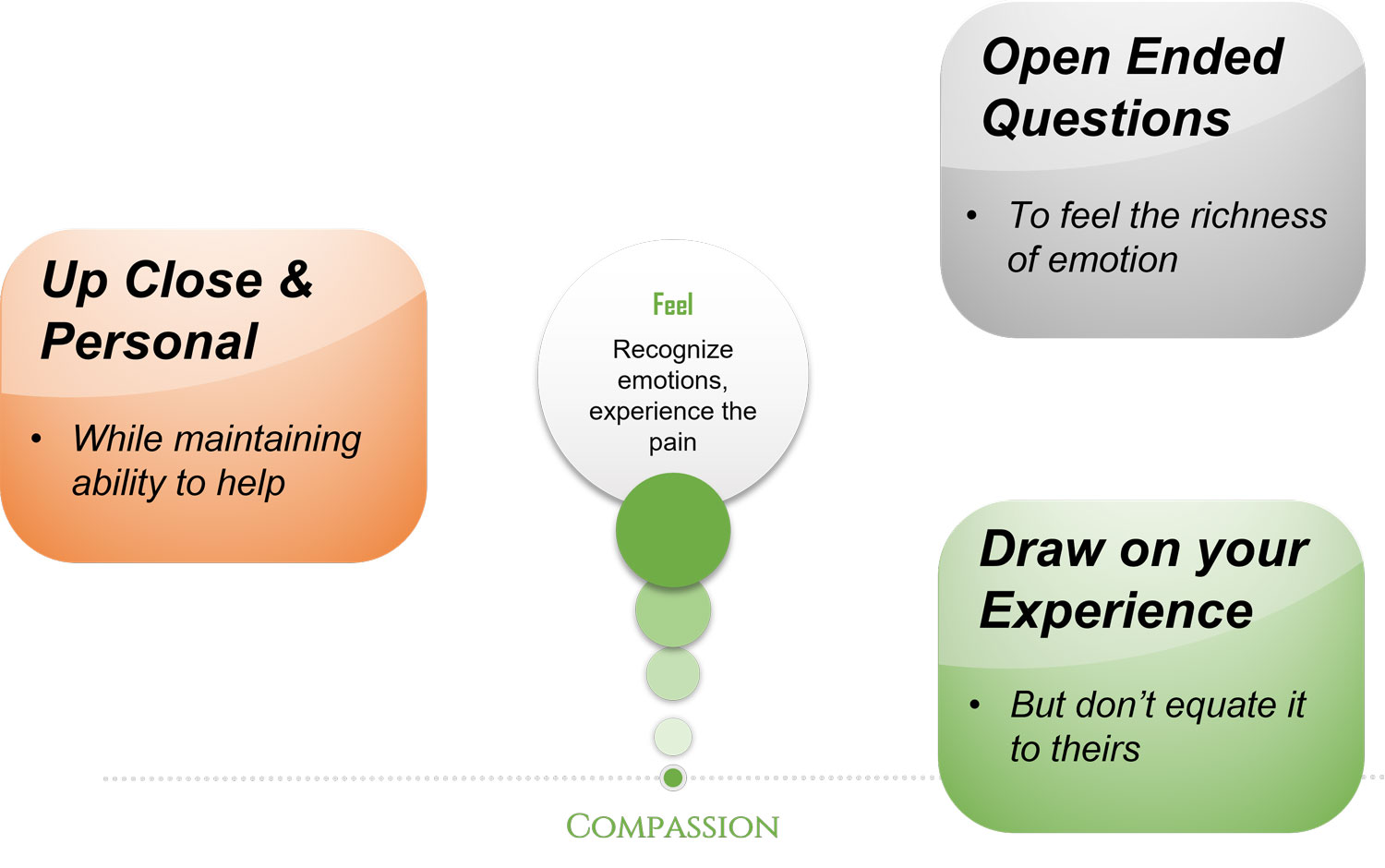

Compassion:

Host: Moving on to the next value of Compassion, in the CORE Online video course you talk about one cannot walk through water and not get wet, does that relate to Compassion?

Expert: Yes it does, to connect with the pain in the person, the professional needs to reach within and connect with something within oneself that knows that feeling. This may even be the pain they have experienced from personal adversity. For the professional, this is a choice, and it is a vulnerable choice. To comprehend the darkness, one must get close enough and feel what that feeling is. The phrase “your pain in my heart” aptly catches how close one needs to get to deliver compassionate care.

Host: But it must be so painful to get up close and personal in this fashion with people in suicidal distress.

Expert: It is a fine balance, close enough, but not so close that the professional gets overwhelmed and is unable to capture hope or help connect the person with the strengths they possess. Another thing to note is that although we encourage professionals to draw on their own pain to walk by the person, we strongly remind them that it does not equate to the pain in the person they are supporting. Emotional pain is unique to the person. Come what may, under no circumstance should the professional make it about themselves. This is about walking with the person in distress.

Host: This balancing act I assume comes with experience, are their techniques and strategies people can take to translate the value of compassion into action?

Expert: For those who struggle with the idea of reaching within, they would need to depend on open questions when attempting to establish the type, extent or source of the pain. Open questions allow for a much richer response. Closed questions like were you terrified will only bring forth a yes or no answer. How was that like for you would bring out the full range of emotions the person is dealing with. The professional can then begin to imagine what it must feel to walk in those shoes. And with time they will develop the ability to connect with compassion.

Host: So time is a key factor in developing this attribute to one’s practice.

Expert: Actually, I will correct myself, time provides experience, but experience on its own does not result in new learning, however if experience is combined with reflective practice, experience turns into new insight. That’s when one gets what I call the ability to “see more and see before.” It’s like an emotional eye, an eye that exists in your heart or your soul, the emotional eye opens when you connect with compassion.

Host: But doing this everyday must take its toll, professionals who are supporting people in suicidal distress round the clock may not want to see with that emotional eye and keep the conversation at an intellectual level.

Expert: That is so true, be mindful of compassion fatigue. Helping should not hurt. If it hurts, take time to replenish your compassion cup. One cannot pour out of an empty cup, if it’s empty, it’s empty, needs a refill.

Host: How will one know it’s empty?

Expert: If connecting with a suicidal person’s pain no longer evokes pain in you, perhaps it is time to heal yourself from vicarious trauma. A carrier in caring is a marathon, and self-compassion is the sustenance that supports a professional to keep connecting with people in suicidal distress over a lifetime. It’s not an easy calling to respond to, but immensely rewarding for those who respond and manage to find the fine balance between compassion for oneself and the other.

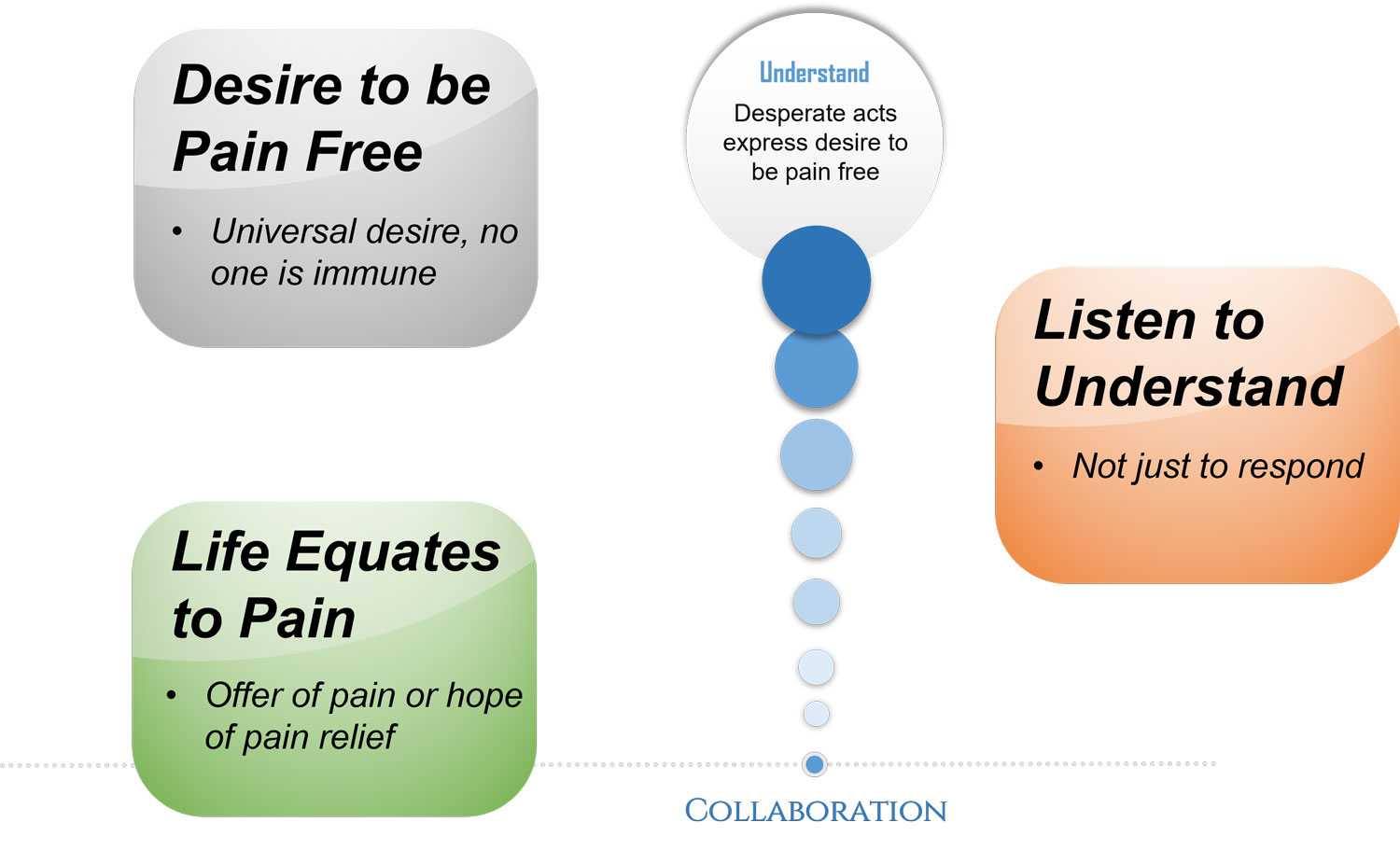

Collaboration:

Host: If one reaches out with true compassion, does it automatically pave the way for the fourth value – collaboration

Expert: It does, a collaborative partnership demands, professionals attempt to understand before they expect to be understood. Many attitudes regarding suicide persist. Some consider it a sin, others a right, some say it takes courage, others consider it cowardice. These beliefs influence the way in which we connect and collaborate with a person in suicidal distress. Some consider it a selfish act, a belief that can significantly impede empathy in the professional.

Host: I have a degree of empathy for those who might think that, like the suicide of a teacher which might leave a whole school of children sad and anxious, or the suicide that leaves behind a widow with three young children.

Expert: Joiner (2010) makes the point that people who attempt suicide are often attempting to help their loved ones and not hurt them. They are astounded by the anguish they cause; in their mind, they had genuinely believed that their suicide will make life easier for others. However misguided, the thought to spare others is hardly selfish (Freedenthal 2018). Selfish or selfless, we can all agree that humans are programmed to reduce pain and suffering.

Host: Yes, that is one thing that is quite easy to agree on, after all who wants more pain in their life, whether it be physical pain like from arthritis or emotional pain like from depression or major life losses or trauma, everyone wants to find ways to reduce the pain.

Expert: As professionals, our offer of help is translated as “persevere with life”, but life equates to pain in the mind of the suffering person. Unless professionals understand this alternative perspective, their offer of help will continue to come across as an offer of more pain rather than an offering of hope, the hope of pain relief.

Host: This takes us back to Optimise Pain Relief

Expert: Yes it does, the point I am making is to co-produce collaborative solutions, listen with the intent to understand, not just to respond to what has been said. Constructing the pain based narrative, elaborated in Optimise Pain Relief, will help significantly live the value of collaboration.

Host: Surely despite one’s best attempt, there will be occasions when a connection cannot be established, or collaborative efforts fail. What happens then?

Expert: A suicidal mind’s distress may make the most competent professional feel ineffective. This unpleasant state triggers a professional’s defences. Being defensive in these situations may entail self-talk, which sounds like, “What can I do if they are not willing to play their part”, “I am not a miracle worker”. The defences protect us against the anxiety which the thought of incompetence provokes.

Host: So how does one address this defensiveness?

Expert: Supervision and reflective practice, that’s where it can be addressed; we have previously talked about the importance of avoiding a power struggle, the same can happen with defensiveness. It can quickly break down any chance one has of collaborative success. We recommend that each professional identifies an early warning system that alerts them to their defences going up (physiological and psychological). This will help acknowledge it, slow down, check negative self talk and take action to break the spiral of defensiveness and collaborative break down. Given a lot of these things are in one’s blind spot, supervision and peer group discussions for reflective practice is essential.

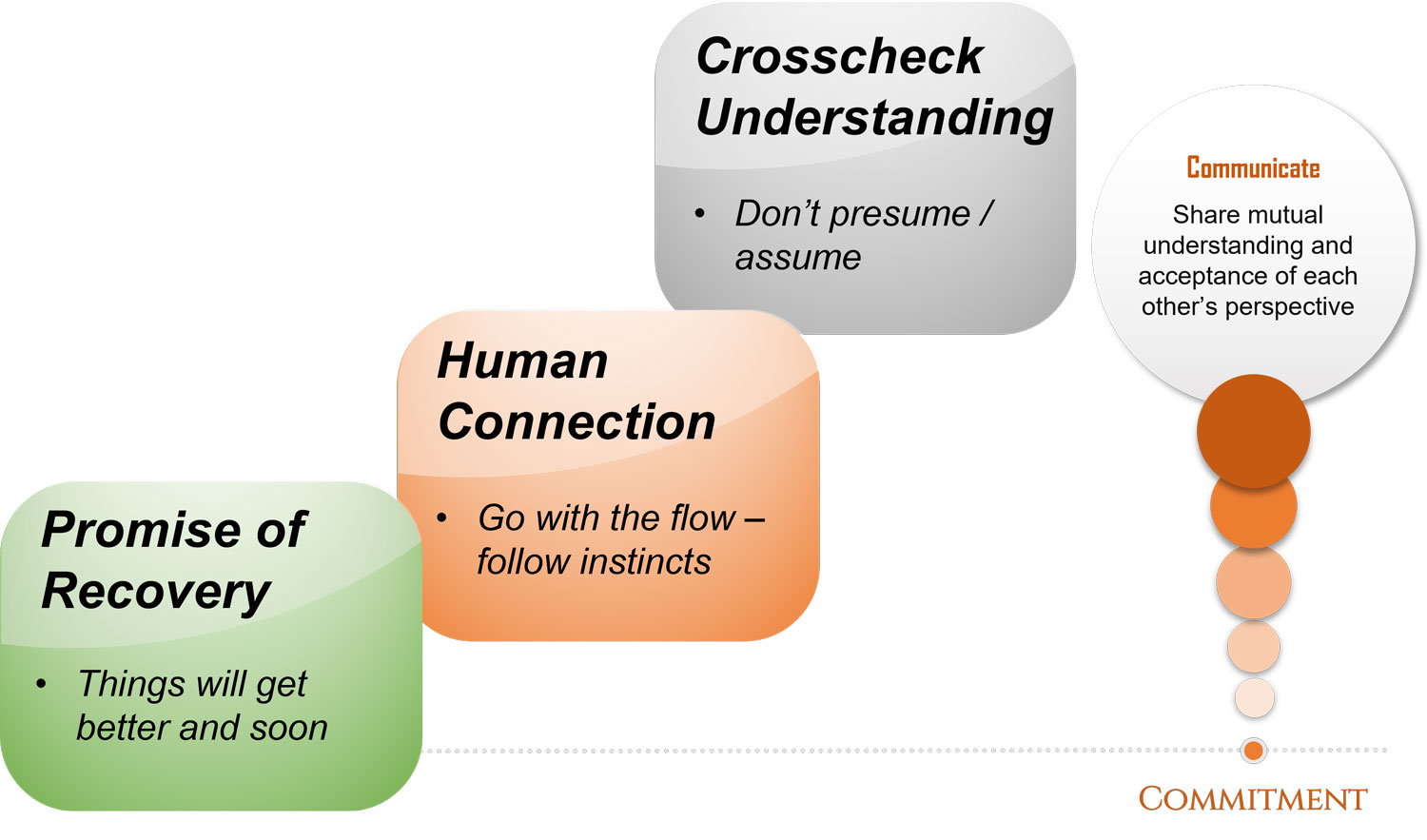

Commitment:

Host: This brings us to the final value Commitment, when you teach you harp on about the promise of recovery. After many of the experiential exercises from the PROTECT workbook, you ask the participant who has been playing the role of the person in distress, did you hear an explicit promise of recovery? Does that relate to this fifth value of commitment?

Expert: Indeed it does, be committed to the promise of recovery and the journey ahead. “Things will get better and soon.”

Host: What if such a promise is not realistic?

Expert: Yes, concerns about how realistic this promise would be creates reluctance in the professionals to make such an explicit declaration. The social determinants of health often feel out of the locus of control of the treating team. There are limitations to the scope of professional practice. Also, in complex health care systems, a professional may only walk part of the recovery journey with the person in distress, handing over care to colleagues in another team or service. Irrespective of these challenges, a commitment to working together towards making recovery a reality gets through. Draw on the person’s strengths and their intimate knowledge of their pain to co-create innovative solutions to life’s overwhelming troubles. Respect the dignity of risk and the person’s right to fail on this journey.

Host: And also, recovery looks different for different people

Expert: It is important to share and crosscheck your understanding as to whether you have truly understood the person’s pain and the extent of the struggle between reasons for living and dying. Do not presume or assume; we do not possess the power to mindread. But be prepared to follow your instincts as the conversation evolves.

Host: When you say follow your instinct, what does that look in practice, particularly when you are in the middle of a conversation?

Expert: Say you ask someone who is struggling with depression are they enjoying life and they say no and you ask what they used to enjoy and they say watching football, the next question isn’t how is your energy or can you concentrate. It is what team do you support and in that conversation about something that matters to the person, a skilled clinician will be able to figure out many more symptoms they may want to address in the treatment plan. So, in conversation be natural, not just what the next question is on the form that needs asking.

Host: Being natural relates back to compassion and collaboration, so in conversation just connect as you would with any other person, but what if the connection highlights two very different points of view.

Expert: In that case be open and candid about your understanding and perception. If different points of view come to light, don’t persevere with your perspective, accept that there are multiple realities and be prepared to agree to disagree. There are many routes to recovery, not just the road that the professional considers to be optimal in terms of risk and safety. And often if the interests and needs get addressed the positions change so keep crosschecking from time to time as to which page one is on.

Host: I am hearing commit to communicating all through the journey.

Expert: Yes this two way communication is particularly important as ever so often, a scenario will unfold, where the professional feels a pain of such intensity in the person that they themselves have a sinking feeling in the pit of their stomach. A realisation dawns; there is not much to live for. When this happens, the gut instinct should be attended to seriously. In the kindest and compassionate way, the profound pain should be acknowledged but without conveying a sense of hopelessness. This is a fairly nuanced communication skill, but one that can help connect with a person in the darkest pit, communication that creates relational safety in those critical moment can be life-saving.

Host: This brings us to the end of episode 10, part 3 of Empathy in Action. In fact the end of the CORE module. In the next episode, we will introduce the different chapters of the ASSESS module and begin with the first Appraise Decisions, specifically how attitudes to suicidal distress may impact the interaction and the decisions we make. You can access all the information at www.progress.guide. We would love to hear your thoughts, you can connect with Manaan on Linked in, or follow our linked in page by searching on linked in for progress.guide, you can email us at admin@progress.guide. We are also on twitter and youtube. Our twitter handle is @GuideProgress. As usual please do follow the podcast, there will be weekly episodes every Friday and share it with your colleagues. Your ratings will help get the word out so please don’t forget to rate us on spotify, apple podcasts or audible or whichever channel you are listening on. Today was a day of catch phrases, some of my favourite ones were, patient is not in the way, patient is the way, listen with fascination, mind open – mouth shut, cant walk through water without getting wet, an explicit promise of recovery, things will get better and soon. What was yours? Tweet it #GuidePorgress. Providing healthcare professionals contemporary knowledge about how to connect and create relational safety is crucial in suicide prevention. Remember together we can make a difference. You can be a hope vector and spread this knowledge at your work. Thank you for joining us today and keep translating empathy into tangible action.

You may also like

19 | Creep Crash Crawl

18 | AWARE 5 – Experience