07| Rethink Risk II – Clear and Imminent Risk

- Posted by Manaan Kar Ray

- Categories Weekly PROTECT Podcast

- Date February 18, 2022

Transcript - Futility of Risk Categorization

Defining Clear and/or Imminent Risk

Host: Good day, I am Mahi, your host for episode 7, part 2 of Risk Rethink. Just a quick recap, We have so far completed two chapters from the CORE module. We used a nautical metaphor, Navigating Rocky Waters to introduce the Care Compass in the first chapter. Care Compass was focused on the balancing act that professionals need to strike between risk and recovery and we hope you have an understanding of how to use the compass to engage a person in shared decision making and capturing hope. Remember to access the diagrams from www.progress.guide/blog or get the PROTECT Guidebook from Amazon to read along while listening to the podcast.

The second, Optimise Pain Relief provided strategies for creating a pain based narrative. The goal is to discover common ground using the language of pain relief between the person who is struggling with suicidal distress and the supporting professional. Both chapters help in creating relational safety by getting the person and their family and friends on board for the recovery journey.

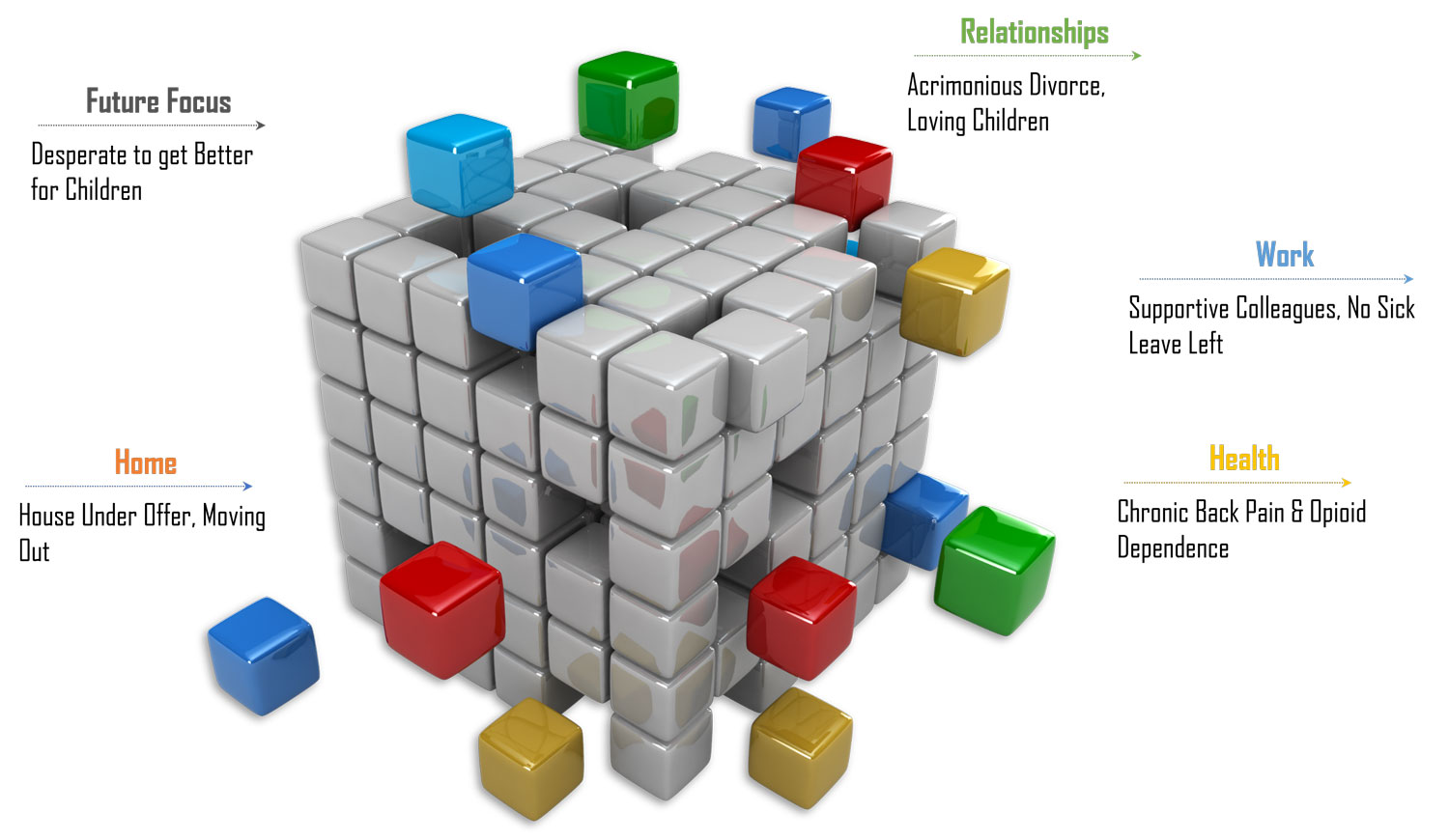

In the third chapter Rethink Risk we have begun exploring the continuum of risk. We also looked at the role of empirically driven risk factors and warning signs and how from a care allocation perspective warning signs trump risk factors. In this episode we will get to grips with a novel way of conceptualising safety in terms of clear and imminent risk and explore the mindset shifts that are needed to work in a recovery oriented way. But let’s pick up where we left off. We introduced you to Shneidman’s cubic model with its situation specificity. This is in sharp contrast to the conventional three-tier risk stratification of high, medium and low propagated by many risk assessment courses. Manaan, in the previous episode we touched on the dynamic nature of risk and how the categorical classification is incredibly static. Is there evidence to support that they are not much use in clinical practice?

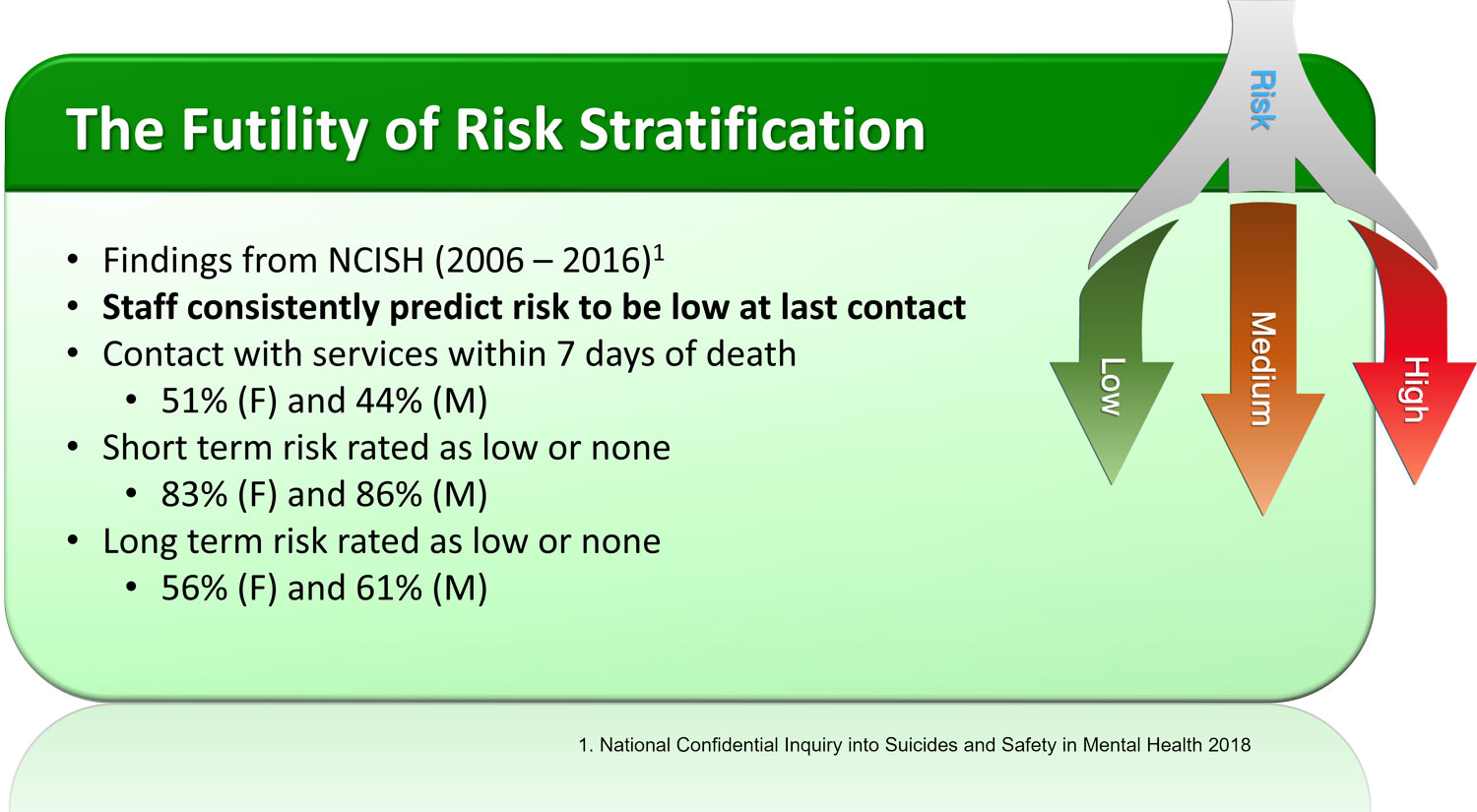

Expert: Actually, there is a lot of evidence. Let’s begin with the UK’s National Confidential Inquiry into Suicides and Safety in Mental Health. The 2018 data showed that staff consistently predict the risk to be low at last contact prior to suicide. Between 2006 to 2016, 51% of females and 44% of males had contact with services within 7 days of death. 83% of females and 86% of males who suicided had their short term risk rated as low or none. Even so called long term risk was rated as low or none in 56% of females and 61% of males.

Host: Why do you think there is such underprediction of risk?

Expert: There can be many reasons for this under prediction. It is possible that those with genuine suicidal intent may share their distress sparingly for fear of detection and intervention. It is also possible that the dynamic nature of risk is such that it fluctuates unpredictably, and it is difficult to foresee the many interactions which can spark a suicidal act. In the ASSESS module, we dedicate an entire chapter to discuss this in detail. It’s a framework called AWARE, in it we describe all the influences on clinical decision making.

Host: Can you share in brief what is covered in AWARE, it might help our listeners contextualise some of the perils of a categorical approach.

Expert: We discovered in the AWARE qualitative study two mental spaces in which clinicians operate, a rational space and a rationalisng one. When clinicians are working in the rational space, all the evidence got mindfully considered before a decision is reached, when working in a rationalising space, they were arriving at a decision early in the assessment process and then sought out evidence to back up their decision.

Host: So is the suggestion that risk categorisation of high, medium and low is a recipe for professionals to operate in the rationalising space.

Expert: Exactly, once a person’s risk is categorised, the assessor sees what they want to see. Risk is a continuum and dynamic in nature. Instead of acknowledging this and safety planning to mitigate against adverse risk fluctuations, it is far easier to justify the low-risk rating by emphasising certain assessment findings and deemphasising others.

Multifactorial Nature of Risk Demands Nuanced Safety Planning

Host: So not only does risk categorisation not add value, from what you have said high, medium, low may actually push a clinician to turn a blind eye to risk related information that they have elicited.

Expert: Yes it is an unintended consequence and it can actually cause harm. Irrespective of whether such rationalising forces are at play or not, the National Confidential Inquiry data shows that over 80% of those who suicided within 7 days had a risk rating of low or none. This raises the question, what is the value-added from such risk stratification.

Host: Other than the National Confidential Inquiry data are their other studies which have similar findings?

Expert: Many in fact, we have our own data that triangulates these findings. Of course, our sample size is much smaller as it pertains to one organisation. We conducted an outcome analysis for case series of people who died by suicide between January 2014 and December 2016 and had contact with a public mental health service within 31 days prior to their death. We found that seventy-five per cent were classified at the last contact as at low risk of suicide. None were identified as being at high risk. While individual risk factors were identified, these did not allow to differentiate between patients classified as low or medium or high risk.

Host: I am assuming this is in an Australian context, are there meta-analyses that combine findings from across the globe?

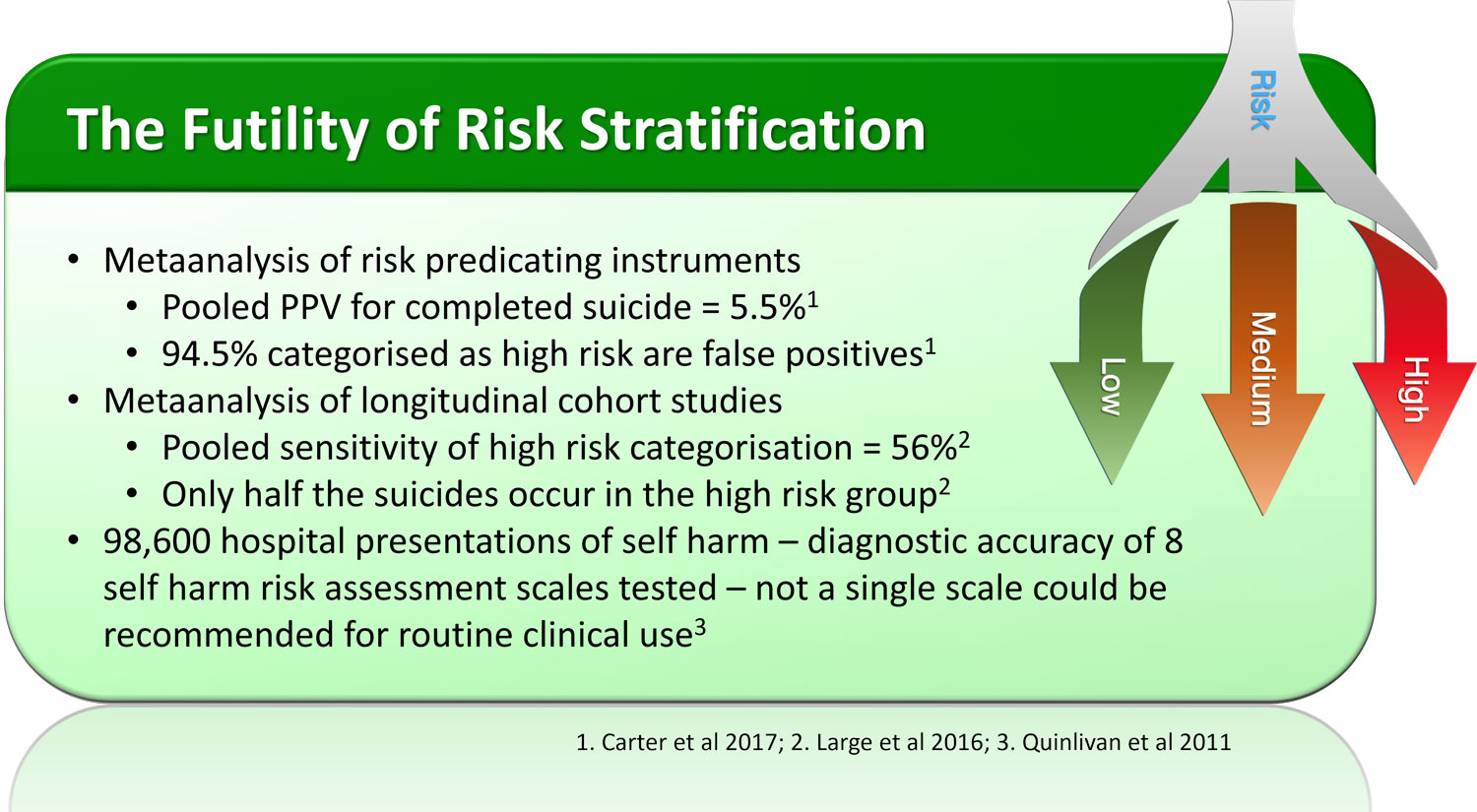

Expert: Again many, there are three studies that I particularly am fond of. One by Carter’s group, the other by Large et al and the third one focuses more on self harm by Quinlivan’s group.

Host: Let’s go through them one by one, tell us about the Carter et al study.

Expert: This is a comprehensive meta-analysis of risk predicting clinical instruments. From initial keyword screening of 1076 studies, they narrowed it down to 70 that were relevant, 52 assessed psychological scales and 17 biological measures, one reported on both. Pooled positive predictive value for completed suicide was only 5.5% for the high risk group. Positive predictive value is the probability that subjects with a positive test truly have the disease, in this case the outcome, so 94.5% of people classified as high risk were false positives. Using the categorical approach, they would end up getting unnecessary treatment, some of which may be fairly restrictive as well involving hospitalisation.

Host: Were Large’s findings similar to Carter’s.

Expert: Yes, but they located longitudinal cohort studies of psychiatric patients or people who had made suicide attempts and were stratified into high-risk and lower-risk groups for suicide. Death by suicide was the outcome. They extracted data regarding effect size, study population and study design from 53 samples of risk-assessed patients reported in 37 studies. Over an average follow up period of 63 months the proportion of suicides among the high-risk patients was 5.5%. The pooled sensitivity of high-risk categorization was 56%, indicating that only over half of the suicides occurred in the high-risk groups and the other half did not.

Host: 95% of the high risk group will not take their life through suicide and the high risk stratification misses half the suicides, then one is left wondering what is the point. But what about self harm, surely the prediction is better for that as it is a more frequent outcome.

Expert: Unfortunately not, Quinlivan conducted a large study investigating the diagnostic accuracy of self-harm risk assessment scales of 98,600 hospital presentations of self-harm. The study revealed that not a single scale performed sufficiently well to be recommended for clinical use.

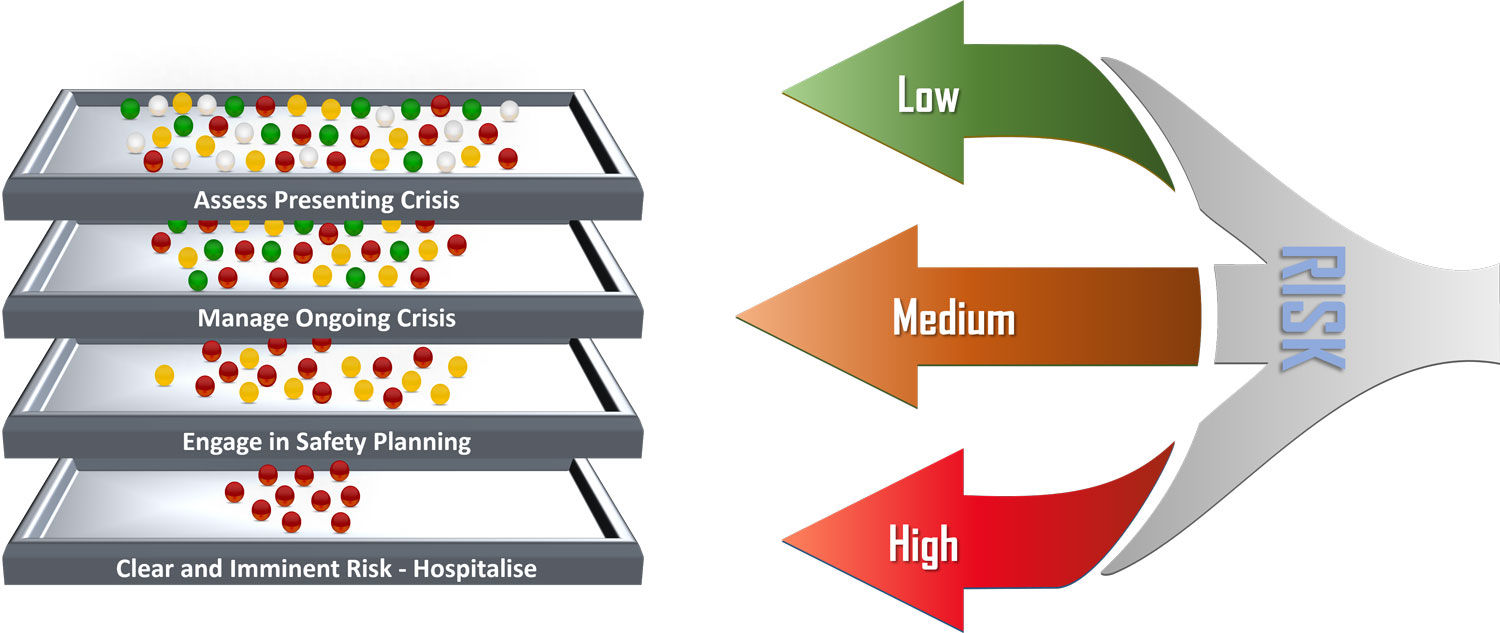

Host: Currently, most suicide risk assessment tools are based on risk stratification. But from what you are saying, the evidence suggests that from a care allocation perspective, many patients will either receive unnecessary treatment or be denied necessary treatment.

Expert: Yes, furthermore, while risk tools use the presence of risk factors for risk stratification, they do not fully account for the dynamic interaction between them (Higgins et al.., 2016). Carter et al. (2017) suggest that it would be more effective to incorporate risk assessment into a comprehensive clinical assessment. Identification of modifiable risk factors could then guide effective interventions (Carter & Spittal 2018). This approach is consistent with the “Needs-based approach” advocated by the National Institute for Health and Care and Excellence (NICE, 2011).

If not high, medium, low, then how do we decide on care allocation?

Host: If not high, medium, low then how should clinicians describe risk?

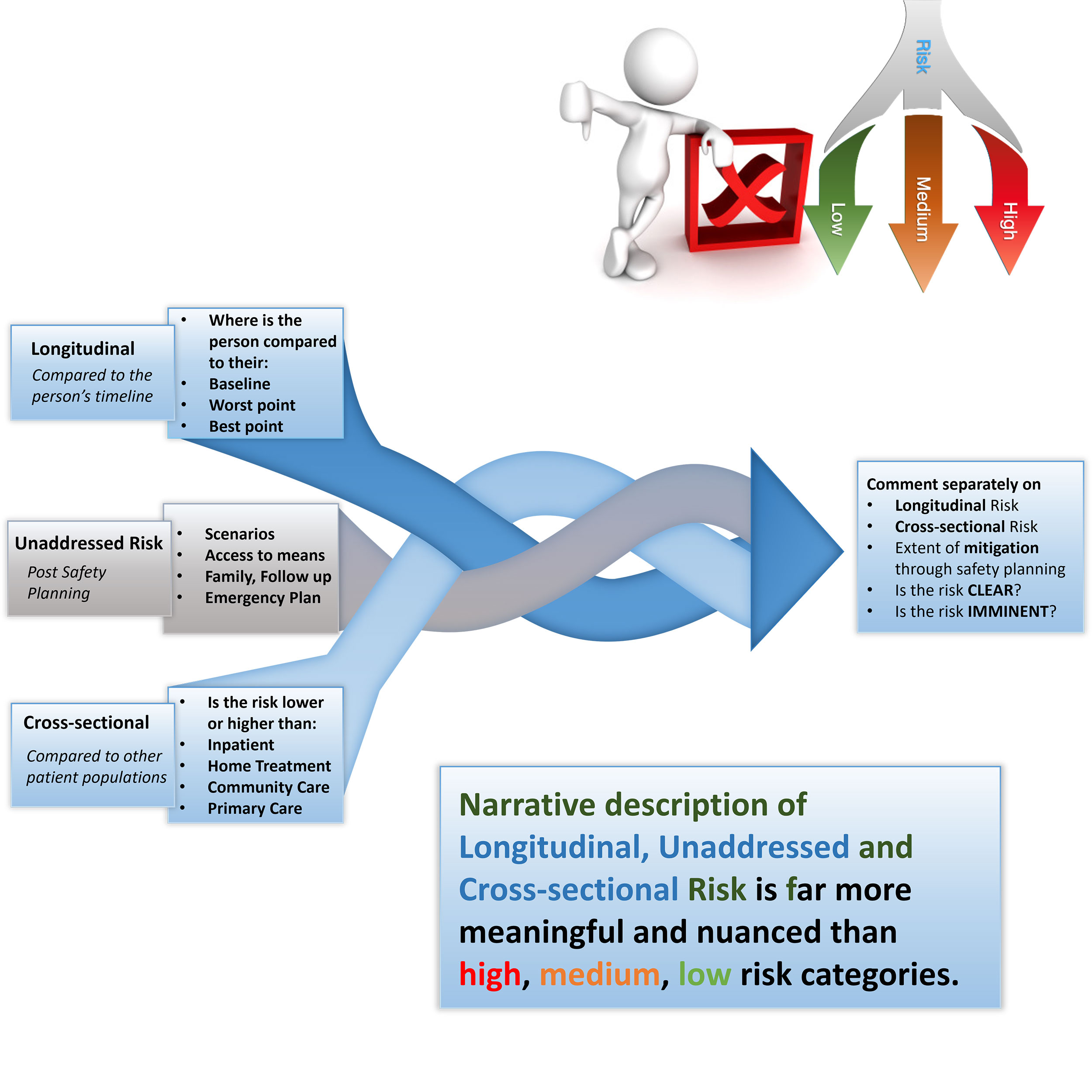

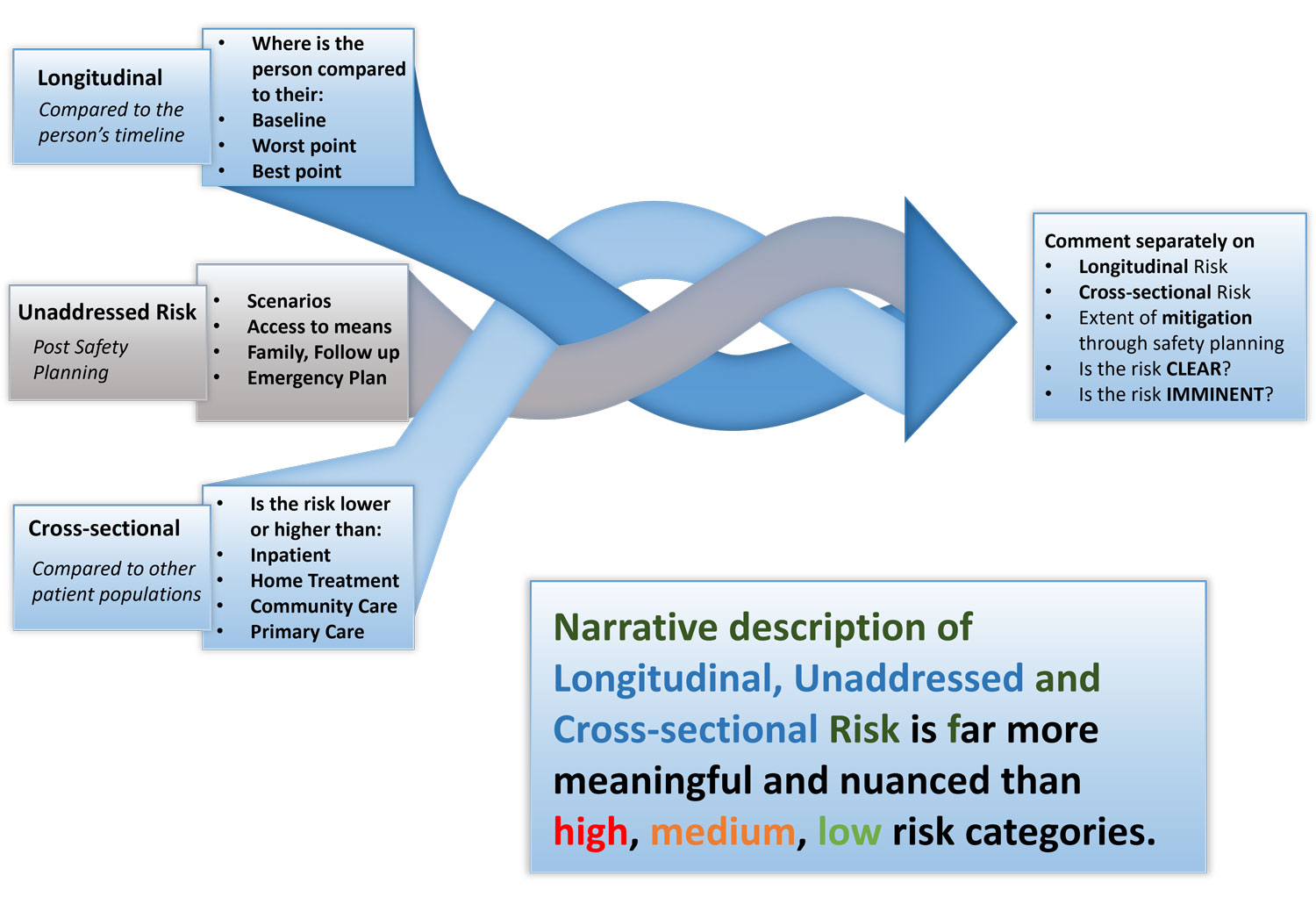

Expert: We recommend a more nuanced approach to determining clear and imminent risk. It involves developing an opinion on longitudinal risk, cross-sectional risk and unaddressed risk, risk that cannot be meaningfully addressed through safety planning.

Host: Longitudinal, unaddressed and cross-sectional, let’s explore each of these, what is Longitudinal risk?

Longitudinal risk

Compared to the person’s timeline

Expert: Longitudinal risk involves developing an opinion on where the person is in comparison to their baseline, worst point or best point. Longitudinal risk may also be used to indicate whether the risk is static, increasing or decreasing. This is dependent on accurate history from the person and collateral information. Essentially, we are formulating an opinion on how the risk is tracking over time for the individual being assessed. So, we find ourselves asking questions like is the risk lower or higher than their baseline, is it getting better or is it progressively getting worse, are they at their worst point or have they turned a corner?

Host: Tell us a bit more about unaddressed risk

Unaddressed Risk

Post Safety Planning

Expert: One cannot develop a meaningful opinion on risk unless safety planning has been attempted. In Chapter 13 in the ASPIRE module we elaborate on SAFE (Scenario Planning, Access to Means, Alcohol and Other Drugs, Family, Friends and Follow up and Emergency Plan). A risk that cannot be mitigated through safety planning has to inform the opinion on clear and imminent risk.

Host: Finally, what is cross sectional risk?

Cross-sectional RISK

Compared to defined patient populations

Expert: This involves developing an opinion on how the person compares to different patient groups, like on an inpatient ward or in-home treatment or community care or with their GP. This is dependent on the assessor knowing risk levels in different tiers of the stepped care model.

Host: It seems to me that longitudinal and unaddressed risk determines cross-sectional risk

Expert: That’s correct, given this is the person’s current risk in comparison to defined groups of patients, the assessor is trying to establish where is treatment best delivered. They are drawing on their current knowledge of the different types of patients that are managed in different care settings.

Host: This sounds like there is subjective judgement involved and it is not an exact science.

Expert: Well, all assessments are subjective, the beauty of this approach is that it can be contextualised to any setting, any culture, any country. Who gets treated where varies based on the norm for that country and resources that are available in that setting? In certain countries or cultures, certain presentations will result in inpatient stay, whereas in others the family and community rallies around the person, not right or wrong just different. Needless to say some of it is often resource driven as well.

Host: You are saying that the system of thinking through Longitudinal risk, unaddressed risk and cross-sectional risk has universal application irrespective of setting.

Expert: Yes, and it is far more nuanced than high, medium, and low. When all three components have been given due attention to, one can formulate an opinion on whether the risk is clear and imminent and where and what treatment should be delivered.

Host: Manaan we have covered a fairly complex topic of rethinking the entire approach to risk. Do you think it will be appropriate to leave the mindset shifts to the next episode?

Expert: I think that’s an excellent good idea, practice change is hard, so it is important for our listeners to internalise why high, medium and low do not add value. Understanding the futility of risk categorisation is really important as that is what is going to bring about progress to practice and people need to really internalise it and not get overwhelmed by another set of mindset shifts that we intend to talk about. They also need to understand what is it that they can do instead. Within the PROTECT training we hammer on the importance of clear and imminent risk, now and the immediate future is where you can make a difference, anything beyond the next week to fortnight, there are way too many factors to try and plan for and meaningfully address. So, steer away from high, medium, low, formulate an opinion on longitudinal, unaddressed and cross-sectional risk and let that intertwined opinion guide you in your decision regarding treatment delivery.

Host: In the next episode we will dive into Chapter 4 Empathy in Action but before that we will discuss the three mindset shifts that are at the foundation of relational safety and a whole new approach to safety and risk. As usual please do follow the podcast, there will be weekly episodes every Friday and share it with your colleagues. Providing healthcare professionals contemporary knowledge about risk assessments is crucial in suicide prevention. You can be a vector for spreading this knowledge at your work. Thank you for joining us and keep rethinking risk and make it a more meaningful exercise for person centred care delivery.

You may also like

19 | Creep Crash Crawl

18 | AWARE 5 – Experience