04 | Using the Care Compass

- Posted by Manaan Kar Ray

- Categories Weekly PROTECT Podcast

- Date January 28, 2022

Hi, I am Mahi, your host for Episode 4: Using the Compass. Manaan the four care quadrants of the care compass that you outlined in the previous episode builds nicely on the nautical metaphor of Navigating Rocky Waters. One can use it to conceptualize and understand recovery and the various pitfalls in the context of suicidal distress, but will you actually use this theoretical framework in delivering clinical care.

Key Conversations:

Expert: In short yes.

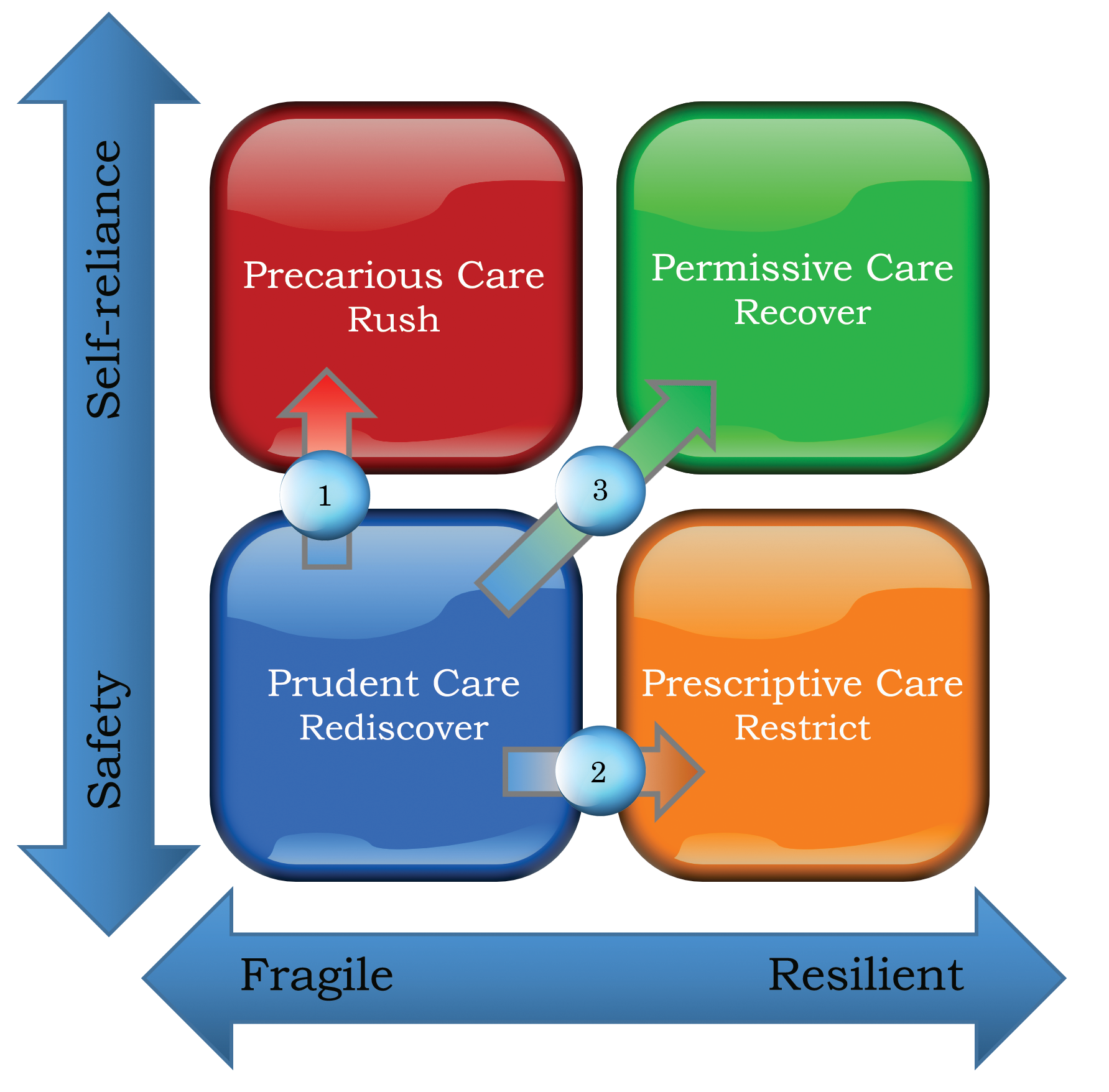

Developing a person-centered care package involves considering the person’s history, current presentation and most importantly, what the person defines as a life that is meaningful to them. This information can be projected onto the compass from the point of view of the person in distress, their family and the professionals. It captures where the person is now and where they are headed and provides the promise of recovery. It is a visual map or prop for some key conversations like capturing hope, understanding risk and safety, resolving differences of opinion.

Host: How will you use the Care Compass to capture hope?

To Capture Hope:

Expert: Safety is the first priority in a suicidal crisis, and it often entails the loss of personal freedoms. Feeling that the locus of control is no longer within one’s sphere of influence engenders a sense of helplessness and may perpetuate suicidal feelings. To mitigate this inherent risk in life-preserving actions, the Care Compass can be used to explain that even in the most restrictive of settings, there are some decisions that the person can make. These decisions might not seem much and generally relate to how they engage with the treatment on offer. Affirming and plotting on the care compass, all positive steps taken by the person in the midst of a crisis serve as a visual reminder that in small but definitive ways, they are influencing the course of events. While receiving prudent care, capturing and feeding back the choices they have exercised support the rediscovery of hope and self-belief.

Host: And both hope and self-belief are crucial in mitigating risk and enhancing safety. Is that what you meant when you said the Care Compass can be used to understand risk and safety.

To Provide an Understanding of Risk and Safety:

Expert: Yes, an extension of capturing hope is an informed discussion on why it is important to strike a balance between risk-taking and the current resilience of the person. Using the transition from prudent care to the remaining three care quadrants, professionals can explain to the person and their families different kinds of risk-taking processes. An honest attempt in helping the person understand the thinking behind the different approaches (Risk Prone, Risk Averse and Positive Risks) may help them see that what they might consider restrictive and describe as risk-averse may be risk-prone in the professional’s mind and vice versa in other situations. Explanations of how the treating team are trying to strike a balance between maintaining safety and letting go generally go down well. This brings them on board for the journey ahead.

Host: I can see what you mean by using the care compass to resolve differences. Will you use the Care Compass to establish how the person themselves believe they are tracking?

To Explore and Resolve a Difference of Opinion:

Expert: Absolutely and if there is a clear difference of opinion between the treating team and the person/support network, the care quadrants and the associated risk-taking approaches can be sensitively explored to establish a middle ground. For example, an individual might feel ready to be discharged, but the treating team might consider this premature. Following the care quadrant discussion, a safe compromise might be reached in which the family take responsibility to mitigate risks for a day leave trial. If successful, this could be followed by overnight leave. The Compass provides the direction around which shared decision making can crystallize, returning the locus of control to the person and guiding future recovery. In Prudent Care, the person is extremely fragile, so positive risks will be small and supervised in nature. With improving resilience, the risks might appear bigger but are in keeping with the same principle of appropriateness.

The converse difference of opinion might also arise; for example, a person may not feel ready to step down into primary care, but the community case manager might feel they are ready. Using the Care Compass, the trajectory they have taken together could be explored. This would often highlight the source of anxiety, making it easier to mitigate. It might involve revisiting the relapse prevention plan, close liaison with the General Practitioner, family coming on board and an agreement for rapid re-access in the first six months. Shared decisions around positive risk support the desired direction of the compass, from the bottom left of Prudent Care to the top right of Permissive Care. When a difference of opinion creeps up, a genuine, honest, empathic attempt to communicate and support the person and their natural circle of support to take ownership of maintaining safety and working towards self-reliance will resolve the dissonance. In terms of constructing a therapeutic alliance, the discussions that precede the shared decision are as important, if not more, than the decision itself.

Host: Are there other uses of the Care Compass?

To Address Culture:

Expert: The care compass can assist in the mindset shift from “what’s the matter with you” to “what matters to you.” Rarely would someone be tipped into suicidal distress over something that does not matter to them. The importance of knowing the person being supported has been repeatedly highlighted (Wilson et al., 2018). The Care Compass could be a vital tool to bring about this mindset shift. Practitioners move from a deficit-based approach of fixing people to an assets-based one of reenabling. It requires practitioners to move from ‘top to tap’ and travel with the person (Kar Ray et al., 2019). When setting and delivering treatment goals in Prudent Care, systematically understanding and addressing what matters to the person will mitigate the dynamic fluctuations in risk that are often missed. Given the issues that are being addressed are important to the person, there will be greater engagement. Safety is an automatic consequence. The same can be said of Permissive Care when engagement with the recovery journey can be considerably enhanced if issues that are meaningful to the person are addressed. Navigating the hearts and minds is important to support anyone with mental health challenges but is particularly so in the person who views suicide as the solution to unbearable psychological pain.

Host: Are there successful examples of such culture change in terms of less restrictive care or positive risk taking?

Expert: The Care Compass was modelled on the practice and learnings within the 333 inpatient setting in Cambridgeshire, UK. National benchmarking data from 2016 showed that the mean proportion of patients admitted involuntarily was 35.1% nationally compared to 19.1% within Cambridgeshire and Peterborough NHS Foundation Trust (Kar Ray et al. 2019). The success in delivering care in partnership and in the least restrictive setting has been replicated at the Princess Alexandra Hospital, Brisbane, Australia, where emergency department mental health staff have been using the 1-2-7 Safety Conversation (detailed in ASPIRE) within the conceptual framework of the Care Compass. Admission rates have dropped from a high of 27.9% of emergency department attendances pre-training in 2019 to a low of 16.5% post-training in 2020 (data being prepared for publication). The care compass helps conceptualize where the current crisis sits within the larger context of the recovery journey. This, when shared with the person in distress and their loved ones, generates hope and the belief that things will get better. Although we cannot conclusively claim that the decrease in admission rates is due to staff’s better understanding of the balance between risk and recovery, we believe that the conceptual framework of care compass supports positive risk-taking in professionals. Like the other dichotomies laid out above, safety and self-reliance are two sides of the same coin. Using the care compass, the professional can seek resonance in the seemingly dissonant positions of life and death, risk and recovery, care and control. The conceptual underpinning of recovery-oriented care in the Care Compass is essential to form the partnership needed for the journey ahead, the journey from pain to pain relief.

Host: So far a lot of the examples and the narrative is around inpatient care or care in an emergency, however most of the recovery journey for people is in the community. Can the care compass be used to discuss and describe some of the hurdles to recovery in the community?

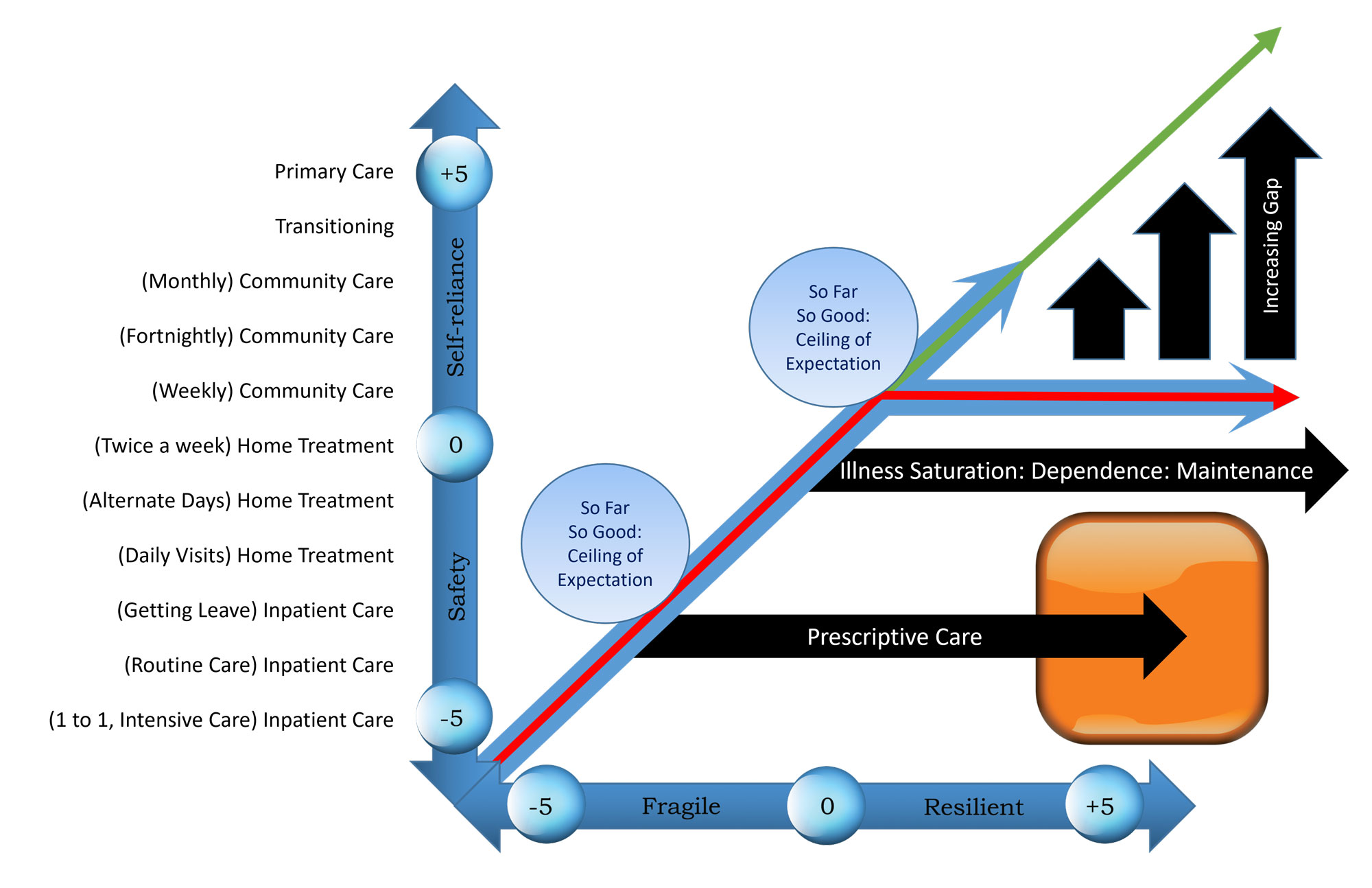

Expert: The answer is a resounding yes. In order to conceptualise this it is really important to look at the diagram, go to www.progress.guide/blog. I will do my best to describe it but it is so much easier when you are looking at it. Although the care compass is not designed to be operationalised in a concrete way, one can map the y axis of safety and self-reliance on the different teams a person may encounter on their recovery journey. The -5 end would then correlate to inpatient care, where the primary focus is on safety. So if you are tracking upwards from the -5 end to the + 5 end one may transitions into intensive home treatment at around -2, which gives way to continuing community care at +1 and finally back into primary care at the +5 end. The x-axis could represent the passage of time. -5 being the time of initial presentation in suicidal crisis and then the person gradually convalescing, becoming increasingly more resilient as they approach the +5 end. If this is the case, the person’s recovery journey, represented by the red arrow, should go from the bottom left to the top right. Secondary care professionals, represented by the blue arrow, should track along, with their role gradually receding and ceasing all together when the person transitions into primary care. Of course, no one’s recovery journey is a straight line, and there will be ups and downs. However, in broad terms, this is what recovery ought to look like, a journey from the lighthouse on the shore where Prudent care is delivered, to the open waters of Permissive care, with the person at the helm, steering through the challenges that life brings forth.

However, on this recovery journey, many hit the ceiling of expectation that care providers have of them.

For the purpose of graphical representation, we have put the marker down around fortnightly appointments with the case manager. Instead of progression to primary care, the person gets stuck in the secondary care system with repeat appointments. The reasons are similar to those outlined in prescriptive care, but irrespective of what causes it, there is a gradual erosion of self-belief and increasing reliance on the professional and services. In time, the professional’s trajectory of fortnightly reviews begins to change the expectations the person living with mental health challenges has of themselves. They no longer have the confidence to sail solo and progress to the top right corner (+5,+5). Instead, they begin to track the professional’s trajectory. Care providers often justify their presence in the person’s life under the title of maintenance treatment, but in reality, this is what illness saturation and dependence looks like.

This can be witnessed in inpatient settings, too, with people getting stuck in the prescriptive care quadrant. Most professionals will recall some patients, where the lack of confidence in safely managing care in the community has resulted in prescriptive care on a psychiatric ward and an endless battle between the services and the person. This is often seen in people with severe and complex borderline personality disorder, where opinion can be extremely divergent as to what is in the person’s best interest. However, generally because of the pressure on beds, professionals are quite mindful of striking a balance between risk and recovery on inpatient wards. But this can easily be overlooked in community care.

Expert (continued): The person’s journey should have been on in the community was upwards and onwards, not just sideways. If services do not mindfully monitor their risk-taking threshold in the community, they will have to deal with the missed opportunity of the person becoming self-reliant and an expert in the management of their condition, represented diagrammatically by the green arrow. The sad truth is that the gap between where the person should have been and where they end up is an ever-increasing gap. Where the person ends up is an iatrogenic effect of services failing to let go in a safe, effective and timely fashion. The longer professionals hold on after their work is done, the larger the gap becomes. It keeps growing with time.

Host: So let me see if I have got this correct. You are suggesting that the Care Compass can be used to constructively review and challenge one own’s practice, or it can be used as a reflective tool within a peer group of mental health professionals. One may be genuinely concerned about the well being of the person they are supporting in the community. However, unknowingly, they may be creating dependence and the community version of institutionalisation. Reflective practice using the care compass can help mind the gap between what a person can be and what they might become if we do not let go in a timely fashion.

Expert: That is spot on. The Care Compass will help strike this balance between risk and recovery. Without risk there is no recovery, with the right care the person has more control.

You may also like

19 | Creep Crash Crawl

18 | AWARE 5 – Experience