Post Action: MEND

The Mend Begins – Holding the Tear with Care

A cloth torn is not a cloth discarded. In the fragile aftermath of a suicide attempt, we stand beside the tear—not to stitch it shut too quickly, but to witness it, gently. This is a phase of quiet holding, where survival has occurred but meaning may still be absent. The MEND model provides clinicians with a way to enter this space with care: not to interrogate or repair prematurely, but to ask, What remains? What hurts? What might still be possible? It allows us to explore four essential domains—meaning, emotion, change, and direction—without rushing to closure. The mend, after all, begins not with thread, but with presence.

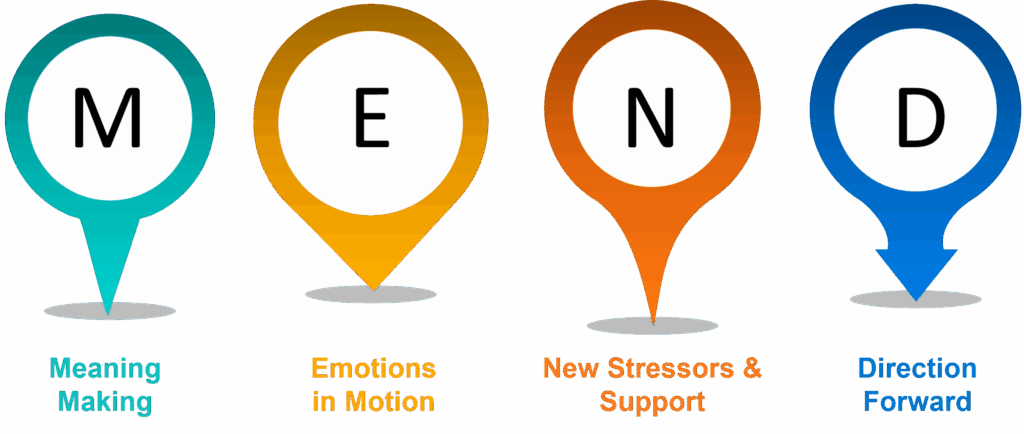

MEND supports clinicians in navigating the post-attempt terrain by tracing four threads of post-crisis reflection:

M – Meaning-Making

E – Emotions in Motion

N – New Stressors & Support

D – Direction Forward

This framework is best used after the acute crisis has passed—often within a few days of the attempt—when the person may be emotionally regulated enough to reflect, but still tender enough to need careful holding.

M – Meaning-Making

In the days after an attempt, some people begin to search for meaning—others resist it. There is no right response. Our task is simply to invite the story: “What has this experience taught you about yourself, if anything?” “Looking back, what were you expecting the outcome to be?” “If you could go back to that day, would you make the same choice—or not?” “Has surviving changed how you see yourself, your life, or your relationships?” Meaning does not always emerge immediately. For some, there is only confusion. For others, regret. And for some, a tentative thread of realisation. The key is to explore how the person holds the experience now—not to define it for them, but to listen as they name it themselves.

E – Emotions in Motion

After an attempt, emotions rarely arrive in neat lines. Relief can sit beside shame. Hope beside numbness. We ask with care: “How have you been feeling emotionally since the attempt?” “When you wake each day now, what tends to be the first thing on your mind?” “Have your feelings changed over the past few days—are they steadier, or still swinging?” “Do you feel more hopeful, more overwhelmed, or about the same?” Emotions in motion do not follow a recovery timeline. They follow pain, memory, relationship, and physiology. Our role is not to push for progress, but to track the shifts—and validate what is felt, even when it contradicts itself.

N – New Stressors & Support

Crisis doesn’t freeze life—it often changes it. Some stressors resolve post-attempt; others worsen. Some supports strengthen; others fade. We explore this gently: “What has changed in your life since the attempt—has anything felt easier, or harder?” “Are you currently receiving any professional help?” “Have you reached out to anyone—friends, family, community—for support, or just to talk?” “Are there new pressures now that weren’t there before?” “Have you found anything—routines, people, small activities—that help, even a little?” This part of the weave is relational and practical. It asks: what presses, and what holds? What threatens to reopen the tear, and what might help protect the mend?

D – Direction Forward

The final strand explores movement. Not grand recovery arcs—but signs, however faint, that the person is facing somewhere. “Since the attempt, how have your thoughts about suicide shown up—if at all?” “Do they feel the same, lighter, or heavier than before?” “Have you made any changes—small or large—to how you go about your days?” “Are there things you’d like to change, even if you’re unsure how to start?” “Would you say you feel like you’re moving forward, staying still, or slipping back?” “Have there been moments—no matter how brief—where hope felt real?” Direction doesn’t demand certainty. It simply asks: what might come next, and what is worth protecting, even if it’s fragile?

Meet Lena – Our Roleplay Character

Lena is a 36-year-old schoolteacher recovering from a recent suicide attempt following divorce and burnout. She is now attending her first follow-up session. She expresses guilt and uncertainty: “I don’t know what I feel. I just don’t want to be this person anymore.” Your task as clinician is to walk with Lena through the four strands of MEND: meaning, emotion, stressors, and forward movement. This is not about finding answers. It’s about honouring the fact that she’s still here—and asking, how does that feel?

What You’ll Take Away from MEND Masterclass

- A framework to explore post-attempt reflection with depth, care, and structure

Skills to hold space for ambiguity—grief, relief, regret, or hope - Capacity to pace conversations sensitively, balancing open inquiry with gentle clarification

- Insights into how people begin to narrate survival—and where that narrative may open paths toward healing

- Practice in identifying new risks, strengthening existing supports, and co-creating personalised safety plans

- A deeper sense of how clinicians can show up—not as fixers, but as steady, listening presences

Join STEPS training to learn how to sit beside the tear—not to stitch it closed too quickly, but to help the person decide how they wish to live with it.

Because mending is not hiding—it is honouring what was torn, and what remains.